This module is a resource for lecturers

Commonalities, differences and complementarity between the global instruments and tools for their implementation

What is the relationship between these instruments and why do several provisions seem to duplicate and overlap with each other? There are, in fact, several commonalities and partial overlaps among these instruments which would call for synergetic approaches to these instruments, as well as some fundamental differences among them. UNODC discussed in a 2016 research paper that the commonalities between these instruments start with their similar objectives (UNODC, 2016). Except for the Firearms Protocol and its parent, the Organized Crime Convention, these instruments have not been purposefully negotiated or constructed as interconnecting instruments. However, they all have broadly similar or compatible objectives: to control different categories of conventional international arms trade and prevent illegal activities.

The broader aims of these instruments are equally similar - mitigating the negative impacts of illicit trafficking in conventional arms on national, regional and international security. For example, the Firearms Protocol notes " the harmful effects of those activities [illicit manufacturing and trafficking of firearms] on the security of each State, region and the world as a whole, endangering the well-being of peoples, their social and economic development and their right to live in peace" (Preamble, Firearms Protocol). Similarly, the Programme of Action refers to the " wide range of humanitarian and socioeconomic consequences and pose a serious threat to peace, reconciliation, safety, security, stability and sustainable development at the individual, local, national, regional and international levels" (Section I, paragraph 2, Programme of Action). The preamble of the ATT notes that " civilians, particularly women and children, account for the vast majority of those adversely affected by armed conflict and armed violence" (Preamble, Arms Trade Treaty).

The instruments clearly reinforce each other. This is evident in the way in which the instruments refer to the other treaties, affirming obligations or noting their complementarity. For example, the preamble of the Programme of Action (PoA) recognizes that the Firearms Protocol " establishes standards and procedures that complement and reinforce efforts to prevent, combat and eradicate the illicit trade in small arms and light weapons in all its aspects". The PoA foreshadows the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) in its commitment by States to " encourage negotiations, where appropriate, with the aim of concluding relevant legally binding instruments aimed at preventing, combating and eradicating the illicit trade in small arms and light weapons in all its aspects, and where they do exist to ratify and fully implement them" (Section II, paragraph 25, Programme of Action).

The ATT specifically contains a provision on the relationship between the ATT and other international agreements in Article 26: " The implementation of this Treaty shall not prejudice obligations undertaken by States Parties with regard to existing or future international agreements, to which they are parties, where those obligations are consistent with this Treaty".

The fact that the ATT specifically mentions other international agreements in its preamble, including the Firearms Protocol, suggests that States view the Firearms Protocol as an international agreement with obligations that are consistent with the ATT. Additionally, the ATT draws upon State parties' existing obligations, affirming those obligations and restating them within a different legal framework. Article 6(2) prohibits transfers that violate a State party's " relevant international obligations under international agreements to which it is a Party". Article 6(2) also makes specific reference to international treaties concerning the authorization and " transfer of, or illicit trafficking in, conventional arms" and related items. This includes the Firearms Protocol. It is noteworthy that Article 6(2) does not create new substantive obligations as it refers to obligations that a State party already has. But the significance of referencing these other obligations is that the ATT subjects those obligations to its regulatory mechanisms required for " transfers". For example, a State party will be required under Article 13(1) of the ATT to report on how it implements Article 6 (2) in its national laws.

Under the PoA, at the national level, States undertake " To put in place, where they do not exist, adequate laws, regulations and administrative procedures to exercise effective control over the production of small arms and light weapons within their areas of jurisdiction and over the export, import, transit or retransfer of such weapons, in order to prevent illegal manufacture of and illicit trafficking in small arms and light weapons, or their diversion to unauthorized recipients" (Section II, paragraph 2, Programme of Action). The PoA is a policy framework and largely does not provide the details on what are " adequate laws, regulations and administrative procedures". However, the preamble of the PoA specifically mentions the Firearms Protocol; in fact, it is the only treaty specific to small arms that is noted. When the PoA speaks of having "adequate laws" in place, it is referring at least in part to the framework provided by the Firearms Protocol (UNODC, 2016).

Differences between the global instruments

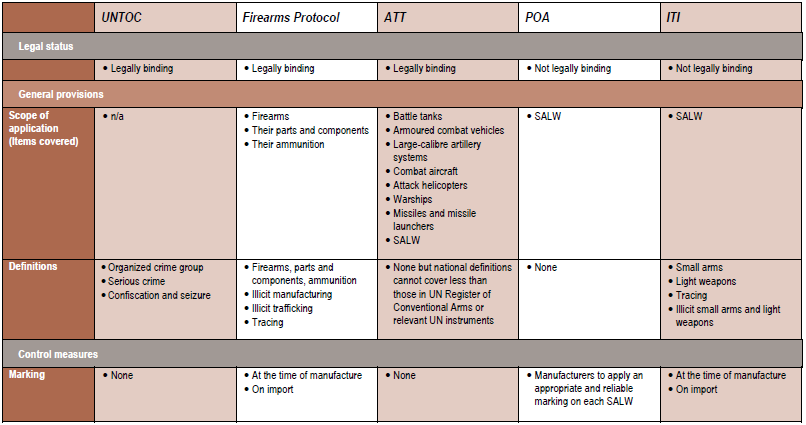

The global instruments on firearms and other conventional arms exhibit also some difference, which can be identified in the scope of their application, the types of activities, the approach towards marking, and the regulation of deactivation, record-keeping and trans-shipment.

The ATT has the widest scope of application among the global instruments and it includes seven categories of weapons, in addition to the category of small arms and light weapons (Article 2(1)). Ammunition/munitions and parts and components are defined in Articles 3 and 4 in relation to these eight categories. Ammunition/munitions and parts and components are also covered by the Treaty to the extent that the former can be fired, launched or delivered by the categories of weapons, and the latter are in a form which provides the capability to assemble the conventional arms. On the other hand, the Firearms Protocol applies only to firearms, their parts and components and ammunition (Article 2). Both the PoA and the ITI include in their scope only small arms and light weapons without reference to their ammunition, parts or components. The debate on the definitions "firearms" and "small arms and light weapons" is outlined in Module 1 on Introduction to Availability, Trafficking and Criminal Use of Firearms,

In addition to the differences and overlap in the types of conventional arms covered by each instrument discussed above, there are also differences regarding the types of activities that are regulated by each. The focus on different activities in each instrument is connected to the varied natures and contexts of each. The Firearms Protocol, as a crime prevention tool, addresses only certain activities that can be linked to the specific criminal offences included within the Protocol. The Arms Trade Treaty regulates the international trade in conventional arms and is therefore focused on activities related to the trade and the possible diversion into the illegal trade. As a result, the Arms Trade Treaty does not focus on enforcement activities or on activities that are not related to the trade (for example, possession). The Programme of Action seeks to address a broad range of activities to prevent, combat and eradicate the illicit trade in small arms and light weapons. The purpose of the ITI is to identify and trace illicit small arms and light weapons (Section 1, paragraph 1). Given this, its primary focus is on marking and tracing activities. Record-keeping, responding to tracing requests and international cooperation are also key activities in the ITI. The activities regulated under the different instruments are summarized in Table 6 below.

|

Firearms Protocol |

Arms Trade Treaty |

Programme of Action |

International Tracing Instrument |

|

|

|

|

Table 6 Types of activities regulated under the global instruments, UNODC, 2016

The instruments also show different approaches towards the implementation of the marking requirements. The purpose of marking is to provide a unique set of marks to a firearm, or other small arms, that identifies it and forms the basis on which records are kept and tracing can be done. The Firearms Protocol, the ITI and the PoA contain provisions about the time when the marking should be applied, whereas the ATT does not take this issue into consideration.

The ITI and Firearms Protocol specify that marking should be applied at the time of the manufacture, on import and on transfer from government stocks to permanent civilian use. Due to the difference in the scope of the two instruments, the ITI referral to marking includes light weapons, whereas the Firearms Protocol is limited only to firearms. The Programme of Action focuses on marking at the time of manufacture. It should be noted that none of the international instruments that establishes marking requirements applies them to parts, components and ammunition.

From the comparative table it is evident that the length of record-keeping is regulated differently with the ITI foreseeing the longest minimum period of 30 years, whereas the Firearms Protocol and the ATT have set the minimum period at ten years. On the other hand, the PoA does not provide an explicit number and specifies that the length of the record-keeping period should be as long as possible.

Finally, the regulations of deactivation and trans-shipment also highlight differences between the global instruments. Deactivation is the process that renders a firearm permanently inoperable. Many States allow the possession (and display) of deactivated firearms by collectors, museums, rifle clubs, etc. Such deactivated firearms are generally subject to fewer controls. Once a State has determined the circumstance where it is lawful to possess deactivated firearms, it must regulate the manner of deactivation. The only instrument that addresses deactivation is the Firearms Protocol. Similarly, trans-shipment is specifically regulated only in the ATT. According to the Kyoto Convention of the World Customs Organization, " trans-shipment" is defined as the customs procedure under which goods are transferred under customs control from the importing means of transport to the exporting means of transport within the area of one customs office, which is the office of both importation and exportation (Article 2, Annex E).

In conclusion, these instruments address the proliferation and misuse of firearms and other conventional arms, their diversion and illicit manufacturing and trafficking from different perspectives. This has resulted in some instruments emphasizing particular elements more than others. For example, the Firearms Protocol takes a crime prevention approach in setting out various offences relating to manufacturing, trafficking and marking of firearms. The Organized Crime Convention provides a significant array of enforcement mechanisms to enable its State parties to address " serious" crimes, including the offences in the Firearms Protocol. The ATT in emphasizing regulatory frameworks provides details on the content of national control systems that enable effective regulation of international transfers. It is these different perspectives that states should draw upon in considering their national laws. These different instruments are important in their potential to complement each other and become " building blocks" in elaborating comprehensive national framework, which are discussed in Module 6 on National Regulations on Firearms.

click on the image to open the full table

Table 7 Comparative summary of international instruments (adopted from "Comparative Analysis of Global Instruments on firearms and other Conventional Arms: Synergies for Implementation", UNODC, 2016)

Next:

Tools to support the implementation of the global instruments on firearms and conventional weapons

Next:

Tools to support the implementation of the global instruments on firearms and conventional weapons

Back to top

Back to top