This module is a resource for lecturers

Key issues

This Module is designed to help lecturers acquaint students with the theoretical underpinnings and practical applications of ethical leadership, taking into account the cultural diversity of contemporary organizations. The Module is structured around three major questions:

- What is ethical leadership?

- Why is ethical leadership important?

- How can ethical leadership be promoted?

It is noted that leadership is sometimes exercised collectively, for example, through an organization. However, this Module focuses on individual leadership. The Module applies to both formal and informal leadership.

Leadership and ethics

Leadership has been defined in various ways (Fleishman and others, 1991). One common definition regards leadership as a process whereby an individual influences a group of individuals to achieve a common goal (Northouse, 2016, p. 16). The following components are central to this definition: (a) leadership is a process, (b) leadership involves influence, (c) leadership occurs in groups, and (d) leadership involves common goals.

For present purposes, the Module refers to the individuals exerting influence as 'leaders', and to those being influenced as 'followers'. While the distinction between leaders and followers is helpful for illustrative purposes, it should be noted that one can simultaneously be a leader in one context and a follower in another context. It should also be noted that leadership can be formal, such as in the case of an elected prime minister or a company's CEO. But there are also cases of informal leadership, when the influence does not derive from a formal authority conferred through rules and procedures. Finally, it is useful to highlight that leaders can be associated with the world of business, politics, popular culture, and other areas of life.

Turning to the concept of ethical leadership, Eisenbeiss (2012) argues that this concept involves setting and pursuing ethical goals and influencing others in an ethical manner. Similarly, De Hoogh and Den Hartog (2009) define ethical leadership as the process of influencing the activities of a group toward goal achievement in a socially responsible way. They focus both on the means through which leaders attempt to achieve goals as well as on the ends themselves.

As discussed in detail in Integrity and Ethics Module 1 (Introduction and Conceptual Framework), the study of ethics generally consists of examining questions about right and wrong, virtue, duty, justice, fairness, and responsibility towards others. From an ethical perspective, according to Ciulla (2014, p. 16), the ultimate point of studying leadership is to answer the question: What is good leadership? The word "good" has two meanings in this context: technically good (or effective) and morally good. This focus on the concept of 'morally good' demonstrates that ethics lies at the heart of leadership studies.

The importance of ethical leadership

Ethical leadership is important for two main reasons. First, leaders have ethical responsibilities because they have a special position in which they have a greater opportunity to influence others and, therefore, outcomes in significant ways. Most people would agree that all of us have a responsibility to behave ethically, but it is clear that leaders are held to higher ethical standards than followers.

The values of leaders influence the culture of an organization or society, and whether it behaves ethically or not. Leaders set the tone, develop the vision, and their values and behaviours shape the behaviour those involved in the organization or society. Therefore, leaders have a significant impact on people and societies. Examples of formal and informal leaders from around the world include Nelson Mandela, Mahatma Gandhi, Malala Yousafzai, Peng Liyuan (First Lady of China), Sheikh Hasina Wajed (Prime Minister of Bangladesh), Yvon Chouinard (the founder of Patagonia), Melinda Gates and Angelina Jolie. However, the impact of a leader is not always positive, as illustrated by Hitler's leadership of Nazi Germany. The impact of his leadership was disastrous for millions of individuals and the world in general.

On a smaller scale, even team leaders can have profound effects on their team members and the organization. All leaders, no matter how many followers they have, exert power. To exert power over other people carries an ethical responsibility. Power is the ability of one person (or department) in an organization to influence other people to bring about desired outcomes. The greater the power, the more responsibility a leader has. Therefore, leaders at all levels carry a responsibility for setting the ethical tone and for acting as role models for others.

Contemporary practice and literature is shifting the focus away from traditional leadership styles, such as charismatic and transactional leadership, and is increasingly focusing on leadership styles that emphasize an ethical dimension, such as transformative, servant, value-based or authentic leadership. In other words, what is regarded today as a 'good leader' is someone who effectively leads towards ethical results and not someone who is simply good at leading (as many ill meaning demagogues can be). It has been argued that this development emphasizes the strong links between ethics and effective leadership (Ng and Feldman, 2015).

Two models can be used to explain the relationship between ethical leadership and effective leadership - the 'interpersonal trust' model and the 'social power' model. The former is attributed to Schindler and Thomas (1993), who argue that interpersonal trust is based on five components: integrity, competence, consistency, loyalty, and openness. Integrity refers to honesty and truthfulness; competence is associated with technical and interpersonal knowledge and skills; consistency is defined as reliability, predictability, and good judgment; loyalty refers to willingness to protect and save face for a person; and openness is the willingness to share ideas and information freely. This model reflects the idea that followers who trust a leader are willing to be vulnerable to the leader's actions because they are confident that their rights and interests will not be abused.

The 'social power' model was developed by French and Raven (1959), who identified five common and important bases of power: legitimate, coercive, reward, expert, and referent. Legitimate power refers to a person's right to influence another person coupled with the latter's obligation to accept this influence; coercive power derives from having the capacity to penalize or punish others; reward power is about having the capacity to provide rewards to others; expert power is based on the followers' perceptions of the leader's competence; and referent power derives from the followers' identification with and liking of the leader. Each of these bases of power increases a leader's capacity to influence the attitudes, values, or behaviours of others.

There are three ways in which a follower may react to these forms of power, according to French and Raven (1959). First, when leaders successfully use legitimate or coercive or reward power (collectively referred to as position power) they will generate compliance. Compliance means that people follow the directions of the person with power, whether or not they agree with those directions. The second way in which followers may react to the use of power, especially the use of coercion that exceeds a level people consider legitimate, is to resist the leader's attempt to influence. Resistance means that employees will deliberately try to avoid carrying out instructions or they will attempt to disobey orders. The third type of reaction to power is commitment, which is the response most often generated by expert or referent power (collectively referred to as personal power). Commitment means that followers adopt the leader's viewpoint and enthusiastically carry out instructions. Although compliance alone may be enough for routine matters, commitment is particularly important when the leader is promoting change (Daft, 2008, p. 365). In general, people tend to identify with an ethical leader. Ethical leadership is not the sole source of referent power, but it is an important one, particularly in an increasingly changing, globalizing, and transparent world.

Ethical dimensions of leadership

The evaluation of leadership from an ethical point of view is influenced by ethical theories and principles of ethical leadership, as well as by practical questions. Ethical theories provide a system of rules or principles that guide us in making decisions about what is right or wrong and good or bad in a particular situation (Northouse, 2016). There are various theoretical approaches to ethical decision-making. Three of the major Western theories were discussed in Module 1: utilitarianism (morality depends on whether the action maximizes the overall social 'utility' or happiness), deontology (morality depends on conformity to moral principles or duties irrespective of the consequences) and virtue ethics (morality depends on perfecting one's character). Practical guidelines for exercising ethical leadership have been created by various scholars. For example, Eisenbeiss (2012) highlights four principles of ethical leadership: humane orientation, justice orientation, responsibility and sustainability orientation, and moderation orientation. Another approach is that of Northouse (2016), who suggests five principles of ethical leadership: respect, service, justice, honesty, and community. These principles are the focus of Exercise 5 of the Module.

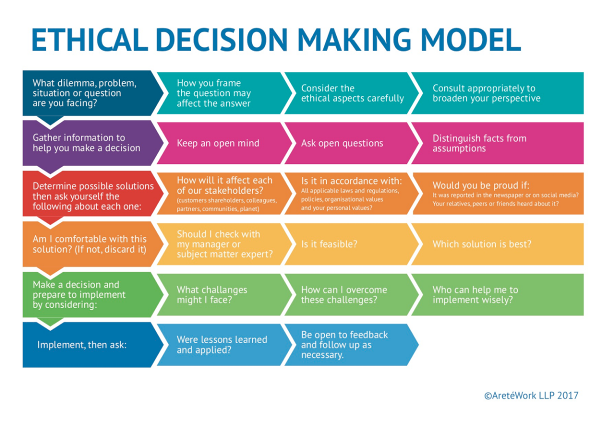

While theories and principles of ethical leadership are pertinent,practical questions are also important for ethical dilemmas, especially since it is not always feasible to apply a detailed theoretical analysis before making a decision. In this regard, it is helpful to use a checklist to guide decision-making. This is sometimes referred to as "ethics quick tests" or ethical decision-making models, both of which have made their appearance in various guises such as codes of conduct of large corporations. The following example of an ethical decision-making model is provided by Hodges and Steinholtz (2018):

Another example is the ethics quick test that is provided by The Ethics Center, an Australian-based non-profit organization. The Ethics Center suggests that we ask the following six questions before we make a decision:

- Would I be happy for this decision to be headlining the news tomorrow?

- Is there a universal rule that applies here?

- Will the proposed course of action bring about a good result?

- What would happen if everybody did this?

- What will this proposed action do to my character or the character of my organization?

- Is the proposed course of action consistent with my values and principles?

Effective leaders are often confronted with impossible dilemmas, where no ideal resolution exists. In such situation leaders need to make difficult decisions that involve sacrificing some goods for the sake of promoting others. A classical example is the decision to go to war, knowing that many people, including civilians, will die. Sometimes this dilemma is known as the dirty hands problem.

Becoming an ethical leader

The issue of ethical leadership is an ancient one. For example, Aristotle argued that the ethical person in a position of leadership embodies the virtues of courage, temperance, generosity, self-control, honesty, sociability, modesty, fairness, and justice. To Confucius, wisdom, benevolence and courage are the core virtues. Applying ethics to leadership and management, Velasquez (1992) has suggested that managers develop virtues such as perseverance, public-spiritedness, integrity, truthfulness, fidelity, benevolence, and humility. Ethical leadership is also associated with the African concept of the sage. Henry Odera Oruka (1944-1995), from Kenya, researched sage traditions of Sub-Saharan Africa and provided an account of wisdom that is distinctly African. The contemporary South African author Reul Khoza provided accounts of ethical leadership from the perspective of Ubuntu which, among other things, feature a communitarian account of virtue originating in Africa. The philosopher Al-Farabi (872-950) provides us insights into ethical leadership from an Islamic perspective. He was born somewhere in modern day Central Asia, and moved throughout the great cities of the Islamic world, such as Baghdad and Damascus. His philosophy was wide ranging, but his insights on leadership can be found in his writings on ethics and politics. In those works, including his famous book The Virtuous City, Al-Farabi argued that leaders should also be philosophers, an idea he drew from the Ancient Greek philosopher Plato. For Al-Farabi, this meant that a leader must not just be a person of action and power, but one who reflects upon what is best for the community which he or she governs. Unlike Plato, he argued that the best city was not a monocultural one, but one which embraced diversity, and the wisest leaders found ways in which peoples of different races and beliefs could live together. Other thinkers have emphasized other sets of virtues, but the differences are not as big as one might think. In fact, people from various cultures may have quite similar views on essential virtues.

Regarding the development of virtues, according to the Aristotelian way, when virtues are practiced over time, from youth to adulthood, good values become habitual, and part of the people themselves. By telling the truth, people become truthful; by giving to the poor, people become benevolent; by being fair to others, people become just. The Confucian way of cultivating oneself begins with obtaining a deep knowledge of how the world works, moves through taking certain actions and ends with one's most ambitious goal - to illustrate virtue throughout the world. This is strongly connected to the idea that 'knowing', 'doing' and 'being' are three interrelated components of an ethical person. In The Great Learning, written around 500 B.C., and the first of four books selected by Zhu Xi during the Song Dynasty as a foundational introduction to Confucianism, Confucius described the process as follows:

The ancients who wished to illustrate illustrious virtue throughout the kingdom first ordered well their own states. Wishing to order well their states, they first regulated their families. Wishing to regulate their families, they first cultivated their persons. Wishing to cultivate their persons, they first rectified their hearts. Wishing to rectify their hearts, they first sought to be sincere in their thoughts. Wishing to be sincere in their thoughts, they first extended to the utmost their knowledge. Such extension of knowledge lay in the investigation of things.

Treviño, Hartman and Brown (2000) argue that ethical leadership comprises two aspects: the "ethical person" and the "ethical manager". One must first be an ethical person in order to become an ethical manager. The managerial aspect refers to a leader's intentional efforts to influence others and guide the ethical behaviour of followers - such as communicating ethical standards and disciplining employees who behave unethically. Ethical leadership relies on a leader's ability to focus the organization's attention on ethics and values and to infuse the organization with principles that will guide the actions of all employees. Treviño and others also identify three measures that effective ethical managers usually take. First, they serve as a role model for ethical conduct in a way that is visible to employees. Second, they communicate regularly and persuasively with employees about ethical standards, principles and values. Third, they use the reward system consistently to hold all employees accountable to ethical standards.

The context in which leaders operate should not be ignored. Even an ethical person with ethical intentions can behave unethically due to behavioural dimensions and or systemic pressures. These issues are explored in depth in Modules 6, 7 and 8. Moreover, ethical leadership may vary in different cultures, including in terms of style and values as well as the manners in which the leader influences followers.

References

- Ciulla, Joanne B. (2014). Ethics, the Heart of Leadership. 3 rd ed. Santa Barbara, California: Praeger.

- Daft, Richard L. (2008). The Leadership Experience. 4 th ed. Stamford, CT: Cengage.

- de Hoogh, Annebel H.D., and Deanne N. den Hartog (2009). Ethical leadership: the positive and responsible use of power. In Power and Interdependence in Organizations, Dean Tjosvold and Barbara Wisse, eds. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Eisenbeiss, Silke Astrid (2012). Re-thinking ethical leadership: an interdisciplinary integrative approach. The Leadership Quarterly, vol. 23, No. 5, pp. 791-808.

- Fleishman, Edwin A. and others (1991). Taxonomic efforts in the description of leader behavior: a synthesis and functional interpretation. The Leadership Quarterly, vol. 2, No. 4, pp. 245-287.

- French, John R. P., Jr. and Bertram Raven (1959). The bases of social power. In Studies in social power, ed. Dorwin Cartwright. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research.

- Hodges, Christopher and Ruth Steinholtz (2018). Ethical Business Practice and Regulation: A Behavioural and Values-Based Approach to Compliance and Enforcement. Oxford: Hart Publishing.

- Ng, Thomas W. H., and Daniel C. Feldman (2015). Ethical leadership: meta-analytic evidence of criterion-related and incremental validity. Journal of Applied Psychology, vol. 100, No. 3, pp. 948-965.

- Northouse, Peter G. (2016). Leadership: Theory and practice. 7th ed. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Schindler, Paul L., and Cher C. Thomas (1993). The structure of interpersonal trust in the workplace. Psychological Reports, vol. 73, No. 2, pp. 563-573.

- Treviño, Linda Klebe, Laura Pincus Hartman and Michael E. Brown (2000). Moral person and moral manager: how executives develop a reputation for ethical leadership. California Management Review, vol. 42, No. 4, pp. 128-142.

- Velasquez, Manuel G. (1992). Business Ethics: Concepts and Cases. 3 rd ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Next page

Next page

Back to top

Back to top