Published in March 2019

This module is a resource for lecturers

The crime of trafficking in persons

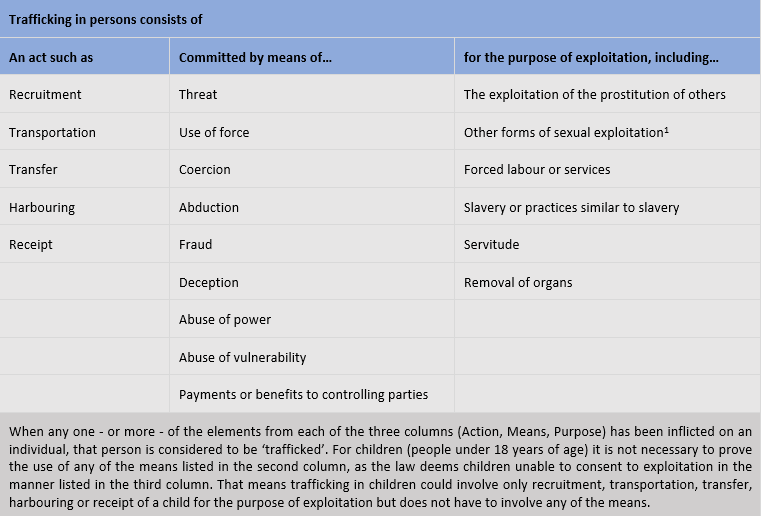

Trafficking in persons is a crime in international law. Article 3(a) of the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons Especially Women and Children provides the sole internationally accepted definition of trafficking in persons:

Trafficking in Persons shall mean the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation shall include at a minimum the exploitation of prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of human organs.

Three elements comprise the offence: the act, means, and the purpose of exploitation, as illustrated in Box 1. These elements and the relevant international legal framework is further explored below.

Box 1: Elements of the offence of trafficking in persons

Source: Adapted from UNODC website

It should be noted that trafficking in persons often intersects with the commission of a range of other crimes (for example, kidnapping, assault, fraud, immigration and labour offences). The added value of having a specific crime of trafficking in persons and related legislation is to identify trafficking as a specific and serious criminal conduct, as well as closing any gaps that might lead to the impunity of perpetrators. Furthermore, anti-trafficking legislation should aim to protect victims and assist them in gaining access to their rights as well as necessary support. States should also promote a focused, collaborative and cross-border approach to fighting this crime. These issues are explored in Modules 7, 8, 9 and 10.

Terminology

'Trafficking in persons' and 'human trafficking' are interchangeable terms. The United Nations adopted the term 'trafficking in persons' when it passed the Protocol against Trafficking in Persons. The Council of Europe uses the term 'trafficking in human beings' as per the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings of 2005. This Module applies the terminology adopted in the Protocol against Trafficking in Persons.

Trafficking in persons is not a modern phenomenon, although the term is a contemporary one. Throughout human history, vulnerable people have been treated as commodities - objectified and exploited for the benefit of others. One of the most obvious historical examples is slavery. Whenever societies tolerate the exploitation of free or cheap labour, trafficking in persons emerges in one form or another (see also Taran, 2006).

The related concepts of "modern slavery" and "modern day slavery" have no internationally agreed definition. States parties to the Protocol are free to use these terms in their national legislation, as long as they still criminalize trafficking in persons in accordance with their obligations under the Protocol. Modern slavery is often used in the context of advocacy as a simpler way of referring to trafficking (notwithstanding the risks of creating stereotypes that neglect other, more subtle forms of control not comparable to "slavery" in the traditional sense).

Profiles of victims of trafficking

The 2018 UNODC Global Report on Trafficking in Persons notes that most of the detected victims of trafficking are identified in their countries of citizenship, that is, in their own country. According to the report, the share of identified domestic victims has more than doubled since 2010, from 27 per cent to 58 per cent in 2016. This finding may indicate an increased capacity of national authorities to identify victims of trafficking at the national level and improved border controls over the years, making it more difficult to traffic victims abroad. Another significant share of the detected victims is trafficked within the same region or subregion (45%), while only one in ten victims were trafficked transregionally. The latter category of victims may include irregular migrants who have left their home countries in search of a better life, who travel without appropriate travel and identification documents, visas or work permits and might not speak the language of the host country, which are factors that may increase their risk of exploitation. Many flee poverty, war and armed conflict, political oppression, natural disasters or poor education and lack of employment opportunities. The report notes in particular the high vulnerability of refugees and people living in conflict-affected areas, where the need to flee war and persecution may be exploited by traffickers to lure them into exploitation. In addition, since UNODC began collecting data on trafficking in persons in 2003, females represent the majority of victims detected globally (see Module 13 for more considerations of the gender aspects of trafficking).

However, these percentages represent only the detected cases of trafficking. Victims of trafficking in persons remain underdetected, especially when it comes to cross-border trafficking.

Numerous factors may make people vulnerable to trafficking in persons. Gender, age, education, disability, a lack of legal documentation and language barriers may all create or increase the risk of exploitation by traffickers. Fundamentally, trafficking is the exploitation of vulnerability (see also Pratt, 2012).

Box 1

Terminology: victim versus survivor

The contention and even dilemma between the use of the term survivor or victim has been widely discussed in the literature on gender-based violence. The term victim is associated with negative connotations. It conveys ideas such as passivity, weakness, powerlessness and vulnerability. In turn, it can have implications in practice by neglecting the agency of the person, and as such the label of victim can be disempowering. In feminist studies and activism, the term survivor - in particular of sexual and domestic violence - was introduced to counter-balance and respond to the negative implications of the term victim and as a way to acknowledge women's agency. However, even the use of the term survivor is not universally agreed. Choosing between the term survivor rather than victim may create a new dichotomy: those who make it and overcome their status of victim and are survivors, and those who do not. As outlined by a key scholar in the field of gender-based and sexual violence, Liz Kelly, this type of dichotomy does not conceptually address the multifaceted nature of victimization (Kelly, 1988). In fact, it neglects the various coping and survival strategies under coercive circumstances (Kelly, 1988) and fails to capture the continuum between agency and victimization.

From a criminal justice perspective, referring to victim of a crime implies the possibility for an individual to seek justice and remedies, having suffered physical or emotional harm as a result of a crime.

Profiles of traffickers and trafficking flows

According to the 2016 UNODC Global Report on Trafficking in Persons, there are at least two broad categories of traffickers: first, those who are members of sophisticated criminal networks and, second, unsophisticated small-time local criminals operating in isolation from organized criminal groups. The former are commonly involved in other serious crimes, such as trafficking in drugs, arms and other illicit commodities, sponsoring terrorism and conflict, and bribery and corruption of State officials.

In some instances, traffickers are former victims of the crime, for whom exploitation has left them with few options. One typical example is that of child soldiers who, in adulthood, remain in armed militia and forcefully recruit others. A second example is of young women trafficked into prostitution who subsequently recruit other young women from their community in return for cash payments from which to reduce their debts to their traffickers.

Qualitative analysis of information from court cases from all over the world reveals that most cases of trafficking involve persons recruited with a promise of a better life away from their community, beyond or within their country's borders (see also SHERLOC Trafficking in Persons Case Law Database).

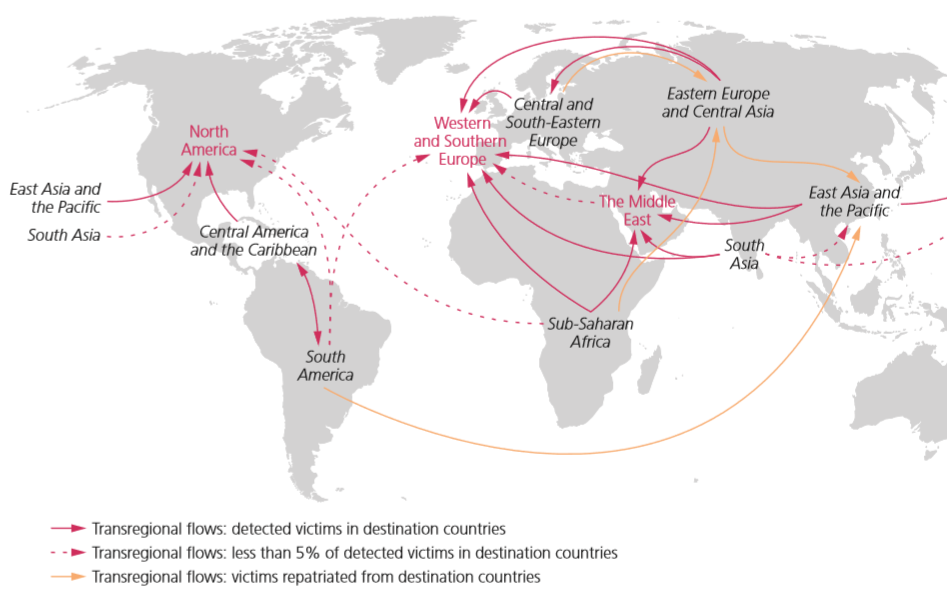

When trafficking in persons is transnational, the majority of victims are trafficked as they attempt to migrate from less wealthy or developed areas to wealthier regions and from rural to urban areas. Because victims are exploited by traffickers as they attempt to relocate to regions that are perceived to offer better opportunities, trafficking patterns tend to reflect migration patterns from poorer to more wealthy nations, as reflected in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Main detected transregional trafficking flows, 2014-2017

Source: UNODC, Global Report on Trafficking in Persons, 2018, p.44

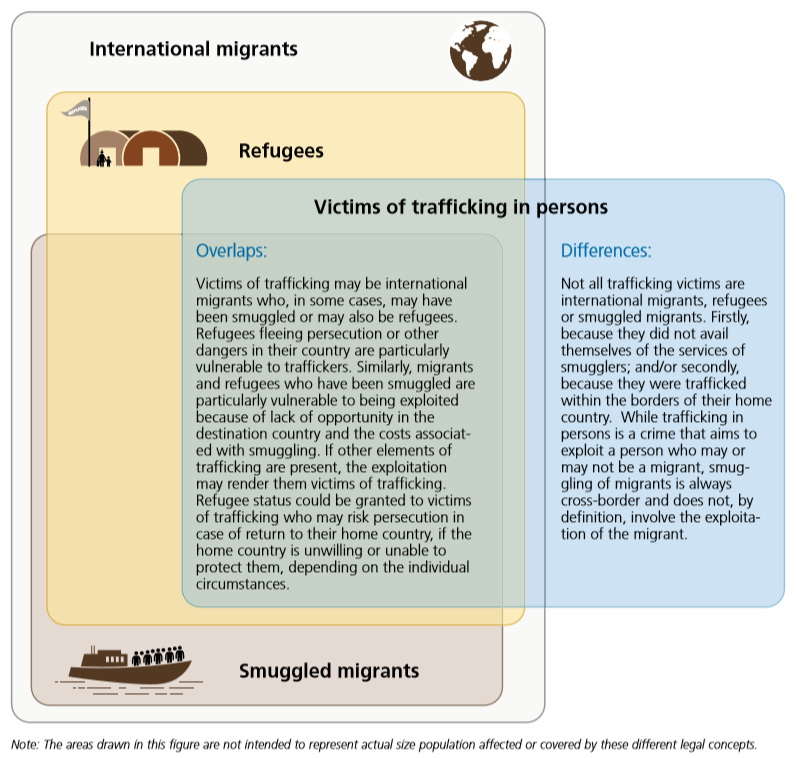

Trafficking and mixed migration

The term "mixed migration" refers to complex movements of people who move for different reasons and have distinct needs, including refugees, smuggled migrants and victims of trafficking (see Module 5). It is common that these people use the same routes and means of transportation on their travels. In large-scale movements, refugees and migrants undertake dangerous journeys, during which they may be subjected to multiple human rights violations at the hands of their smugglers, traffickers and other criminals. In addition, throughout their travels, they may fall in and out of different legal categories and, hence, different protection frameworks may apply to them in the context of their changing circumstances. For instance, they may be recognized or become a refugee in one country, become stateless due to arbitrary deprivation of their citizenship, and ultimately become victims of trafficking ( UNODC, 2016). In this context, it is important to consider some important distinctions and overlaps as illustrated in Figure 2 and addressed later in this Module (see also Module 5).

Figure 2: Overlap between smuggled migrants, refugees and victims of trafficking

Source: UNODC, Global Report on Trafficking in Persons 2016, p. 17

Evolving trends, patterns and strategies of traffickers

Various strategies are employed by traffickers to recruit and exploit victims, ranging from the simple false promise of a job to kidnappings. Often, they gain the confidence of victims through a combination of deception and manipulation. At times, unscrupulous employment agencies deceive workers into entering abusive work situations; what first seems to be a legitimate job is in fact exploitative (see also UNODC, 2015). Women and children are particularly vulnerable to trafficking and may be trafficked by their own communities, families and in public places of business and commerce. Desperate families may even resort to selling their children to traffickers for the promise of immediate payment ( The Protection Project, 2013).

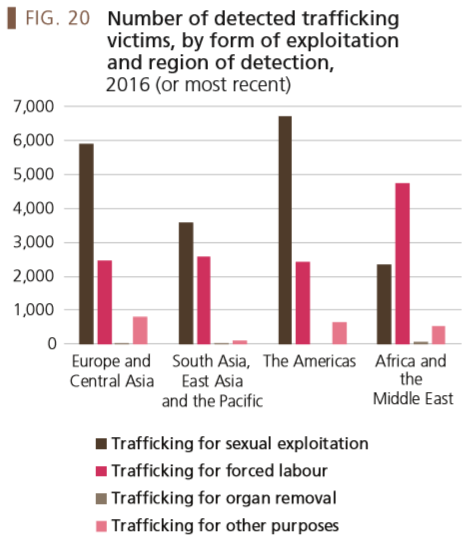

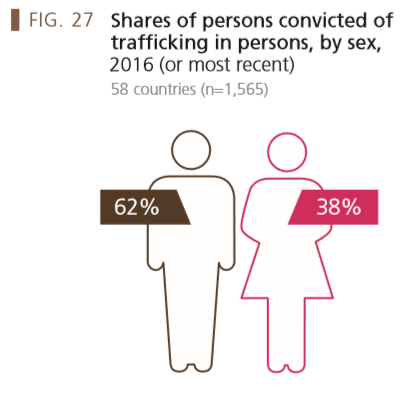

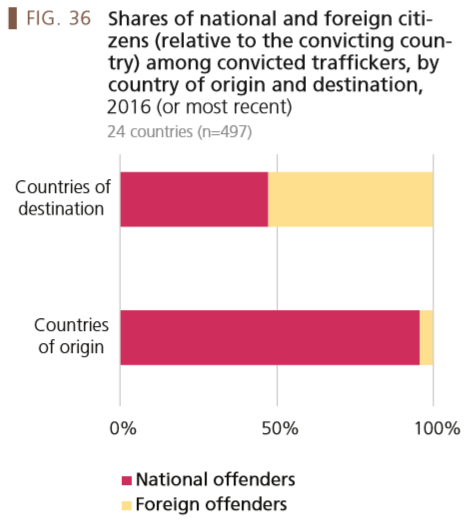

Trafficking trends, patterns and strategies evolve over time and adapt to new demands, challenges, social and political realities and law enforcement responses. Figure 3 illustrates some of the trafficking patterns highlighted in the 2018 UNODC Global Report on Trafficking in Persons. The detected forms of exploitation vary from one region to another (see Figure 3 - Fig. 20). Trafficking for sexual exploitation remains the most detected form of trafficking globally. This may be explained by the fact that law enforcement authorities tend to give priority to investigating this form of exploitation in some regions. The 2018 Global Report also shows that the majority of convicted traffickers are men (see Figure 3 - Fig. 27). Interestingly, the majority of convicted traffickers in destination countries are foreign offenders, while in origin countries they are predominantly nationals (see Figure 3 - Fig. 36). As explained in the 2016 UNODC Global Report on Trafficking in Persons: "a closer look at the citizenships of foreigners convicted of trafficking in persons in destination countries reveals a general pattern. The citizenships of these offenders broadly mirror the citizenships of the victims detected there. In other words, the nationality profiles of offenders are closely connected to the profiles of the victims they traffic. Sharing a culture and/or language background could lead victims to more readily trust citizens of their own country when discussing 'opportunities' abroad. This might be particularly pronounced in the case of women recruiting other women".

Figure 3: Trafficking trends

|

|

|

Source: UNODC, Global Report on Trafficking in Persons, 2018, pp. 29, 36, 37.

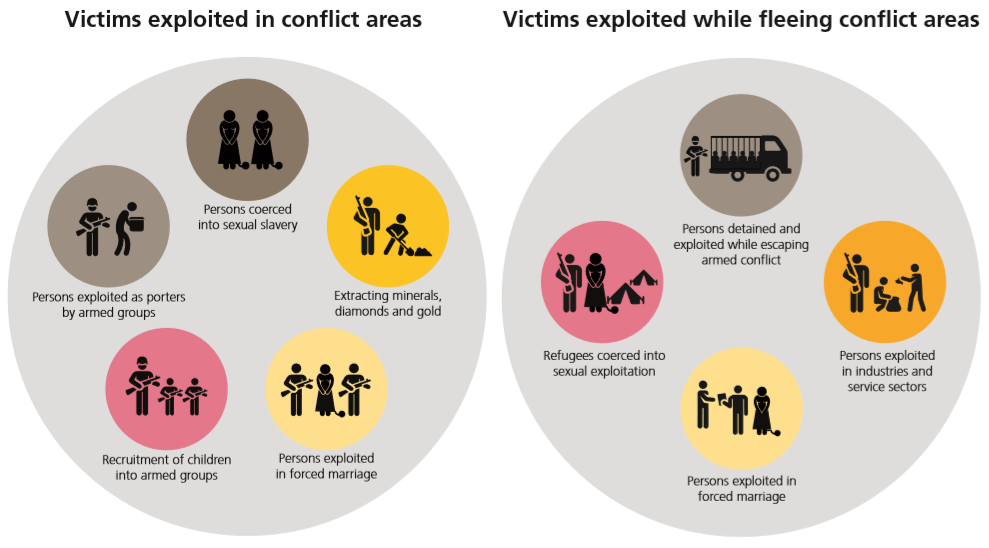

The 2018 Global Report on Trafficking in Persons also highlights the particular vulnerability of people living in or fleeing conflict areas. Over the past 30 years, more and more countries have experienced violent conflicts, leading the international community to pay greater attention to trafficking in persons in the context of armed conflict in recent years. Figure 4 below shows the reported forms of trafficking directly and indirectly related to armed conflict.

Figure 4: Reported forms of trafficking in persons directly and indirectly related to armed conflict

Source: UNODC, Global Report on Trafficking in Persons, 2018, p.12.

Countering trafficking in persons

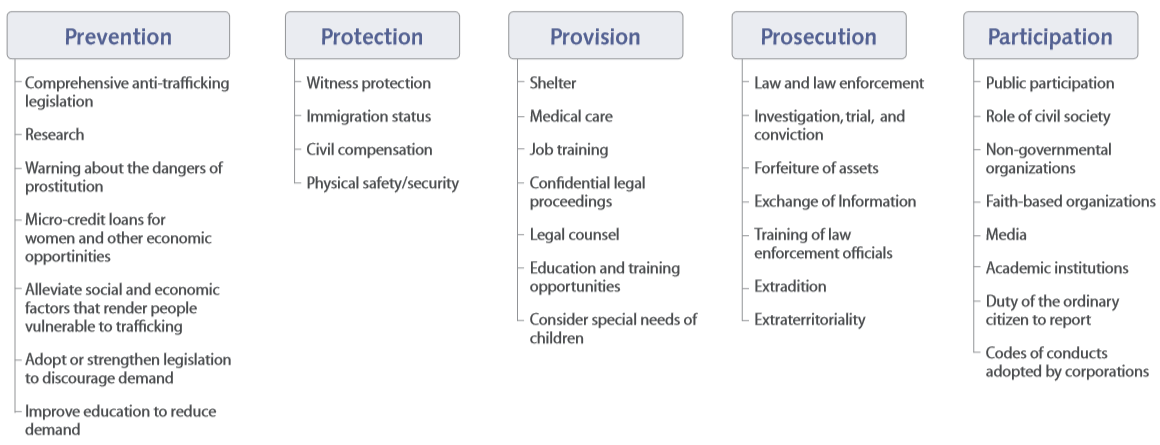

The international community recognizes that combating trafficking in persons requires a hoistic and multidisciplinary approach, involving numerous complementary actors, expertise and strategies. The increasingly transnational scope of trafficking also requires cross-border, cooperative approaches to investigation and prosecution of traffickers (see Bales, 2004). Furthermore, new strategies must be developed and implemented to decrease the vulnerability of potential victims and the opportunities for traffickers to exploit them. A goal should also be to increase the risks and costs to traffickers of engaging in such conduct.

The various components of such a holistic approach (as schematically presented in Figure 5) will be addressed in detail in subsequent Modules of this E4J University Module Series.

Figure 5: Categories of counter-trafficking activities/strategies

Source: Comprehensive Legal Approaches to Combatting Trafficking in Persons: An International and Comparative Perspective (2006), The Protection Project, p. 14.

Next:

The international legal framework: The Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons Especially Women and Children

Next:

The international legal framework: The Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons Especially Women and Children

Back to top

Back to top