- Aggravating and mitigating factors

- Sentencing options relating to organized crime

- Alternatives to imprisonment

- The death penalty and organized crime

- Backgrounds of convicted offenders

- Confiscation

- Confiscation in practice: responding to the movement of criminal assets

- Summary

- References

Published in May 2018

Regional Perspective: Pacific Islands Region - added in November 2019

Regional Perspective: Eastern and Southern Africa - added in April 2020

This module is a resource for lecturers

Confiscation

Some criminals might be content to serve time in prison, if they know their assets will be available upon release, or that their non-incarcerated families may continue to enjoy the proceeds of crime. This is why confiscation of assets is such an important measure to prevent and combat organized crime. It is also an equally important tool to prevent organized crime infiltration of the legal economy.

Confiscation is also known as forfeiture in some jurisdictions. The two terms will be used interchangeably in this Module. Confiscation of assets or property is the permanent deprivation of property by order of a court or administrative procedures, which transfers the ownership of assets derived from criminal activity to the State. The persons or entities that owned those funds or assets at the time of the confiscation or forfeiture lose all rights to the confiscated assets (FATF, 2017; McCaw, 2011; Ramaswamy, 2013).

The large revenues generated from organized crime activity can affect the legitimate economy and in particular the banking system adversely through untaxed profits and illicitly funded investments. Furthermore, even after having invested in the legal economy, organized criminal groups often continue to use illicit tools and methods to advance their business, potentially pushing other businesses out of the market. Confiscation of assets is a way to undermine the fiscal structure and even the survival of an organized criminal group by seizing illicitly obtained cash and any property derived from criminal activity (Aylesworth, 1991; Baumer, 2008; U.S. Executive Office for Asset Forfeiture, 1990).

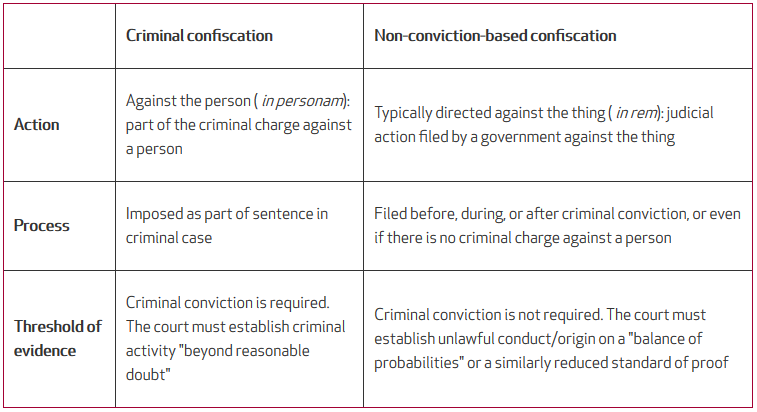

Confiscation occurs under one of two types of proceedings: conviction-based confiscation or forfeiture and non-conviction-based confiscation or forfeiture. They differ in the level of proof required for it to take place. Conventionally, non-conviction-based confiscation requires a standard of proof that is lower than the standard required to obtain a conviction in a criminal court.

Conviction-based confiscation or forfeiture: confiscation by the State of proceeds of a crime for which a conviction of an offender has been recorded. This is also called criminal confiscation or forfeiture in some jurisdictions.

Non-conviction-based confiscation or forfeiture: asset confiscation or forfeiture in the absence of the conviction of the wrongdoer. The term is often used interchangeably with civil confiscation or forfeiture.

Furthermore, States might decide to adopt a value based approach to confiscation, which enables a court to impose a pecuniary liability (such as a fine), once it determines the benefit derived directly or indirectly from the criminal conduct. Value-based confiscation is also included in article 12 (1)(a) of the Organized Crime Convention. It is also worth mentioning that, in some countries, assets may be confiscated even if they are not directly linked to the specific crime for which the offender has been convicted, but clearly result from similar criminal activities (i.e. extended confiscation).

Growing use of confiscation offers the opportunity to disrupt continuing illicit enterprises and to curtail the effect of large amounts of illicitly obtained cash on the economy. There has been a growing body of case law and policy regarding the seizure and disposition of property in asset forfeiture cases.

Concerns regarding the seizure and disposition of property include:

- Lawfulness of confiscation.

- Protecting the rights of third parties.

- Management and disposition of seized or confiscated assets.

Lawfulness of confiscation

Every jurisdiction has specific powers and limits to guide the confiscation of assets. The procedures permitted correspond with the legal traditions in the country. In some civil law jurisdictions, the power to order the restraint or seizure of assets subject to confiscation is granted to prosecutors, investigating magistrates or law enforcement agencies. In other civil law jurisdictions, judicial authorization is required.

In common law jurisdictions, an order to restrain or seize assets generally requires judicial authorization (with some exceptions in seizure cases). Legal systems may have strict obligations to give notice to investigative targets, such as when a search or production order is served on a third party such as a financial institution. That third party may be obliged to advise their client of the existence of such orders, which means that the client would be forewarned about an investigative interest. That must be taken into consideration when taking steps to secure assets or use coercive investigative measures (UNODC, 2012).

The legal principle behind confiscation or forfeiture is that the government may take property without compensation to the owner if the property is acquired or used illegally. There are several broad mechanisms for accomplishing this, however the three predominant types of processes used to confiscate property are: administrative (no conviction), property or criminal (conviction-based), and value-based (UNODC, 2012).

Conviction-based (or criminal) confiscation

In a conviction-based confiscation, property can only be seized once the owner has been convicted of certain crimes. Criminal confiscation is a common approach to asset confiscation in which investigators gather evidence, trace and secure assets, conduct a prosecution, and obtain a conviction. Upon the conviction, confiscation can be ordered by the court. The standard of proof required (normally proof beyond a reasonable doubt) for the confiscation order is often the same as that required to achieve a criminal conviction.

|

Onus of proof Article 12 (7) of the Organized Crime Convention states that States parties may consider the possibility of requiring that an offender demonstrate the lawful origin of alleged proceeds of crime or other property liable to confiscation, to the extent that such a requirement is consistent with the principles of their domestic law and with the nature of the judicial and other proceedings. Similarly, FATF Recommendation 4 states that countries should consider adopting measures, which require an offender to demonstrate the lawful origin of the property alleged to be liable to confiscation, to the extent that such a requirement is consistent with the principles of their domestic law. It is best practice for countries to implement such measures, consistent with the principles of domestic law (FATF, 2012). The following are two examples of how such measures may be structured. When considering confiscation, the court must decide whether the defendant has a "criminal lifestyle". A defendant will be deemed to have a criminal lifestyle if one of three conditions is satisfied. There has to be a minimum total benefit for conditions (2) and (3) below to be satisfied. The three conditions are:

The court is required to calculate benefit from criminal conduct using one of two methods: 1) General criminal conduct ("criminal lifestyle confiscation"): This method is used when the defendant is deemed to have a criminal lifestyle. The court must assume that:

Where the criminal lifestyle condition is satisfied, the burden of proof in respect of the origin of the property is then effectively reversed (i.e. the prosecution has met its evidential obligation and the defendant has to prove on a balance of probabilities that a particular asset, transfer, or expenditure has a legitimate source). 2) Particular Criminal Conduct ("criminal conduct confiscation"): This method is used when the defendant is not deemed to have a criminal lifestyle. This requires the prosecutor to show what property or financial advantage the defendant has obtained from the specific offence charged. The law permits the prosecutor to trace property or financial advantage that directly or indirectly represents benefit (for example, property purchased using the proceeds of crime). There is no minimum threshold for this method of calculation of benefit. |

Non-conviction-based (or administrative) confiscation

A non-conviction-based confiscation occurs independently of any criminal proceeding and is directed at the property itself, having been used or acquired illegally. Conviction of the property owner is not relevant in this kind of confiscation.

Administrative confiscation generally involves a procedure for confiscating assets used or involved in the commission of the offence that have been seized in the course of the investigation. It is most often seen in the field of customs enforcement at borders (e.g., bulk cash, drug, or weapons seizures), and applies when the nature of the item seized justifies an administrative confiscation approach (without a prior court review). This process is less viable when the property is a bank account or other immovable property. The confiscation is carried out by an investigator or authorized agency (such as a police unit or a designated law enforcement agency), and usually follows a process where the person affected by the seizure can apply for relief from the automatic confiscation of the seized property, such as a court hearing. All proceeds of crime are subject to confiscation, which has been interpreted to include interest, dividends, income, and real property, although there are variations by jurisdiction (for more information, please see StAR's " A Good Practice Guide for Non-conviction-based Asset Forfeiture").

Whereas the Organized Crime Convention does not make reference to this type of confiscation, the Convention against Corruption includes it in article 54 (1)(c), which encourages States to "consider taking such measures as may be necessary to allow confiscation of [property acquired through or involved in the commission of an offence established in accordance with this Convention] without a criminal conviction in cases in which the offender cannot be prosecuted by reason of death, flight or absence or in other appropriate cases".

Value-based confiscation

Some jurisdictions elect to use a value-based approach, which is a system where a convicted person is ordered to pay an amount of money equivalent to the value of their criminal benefit. This is sometimes used in cases where specific assets cannot be located. The court calculates the benefit to the convicted offender for a particular offence. Value-based confiscation allows for the value of proceeds and instrumentalities of a crime to be determined and assets of an equivalent value to be confiscated.

Protecting the rights of third parties

Concern arises regarding the rights of individuals not involved in criminal activity, but whose property is used in, or derived from, the criminal activity of others (Friedler, 2013; Geis, 2008; Gibson, 2012; Goldsmith and Lenck, 1990). This might include uninformed lien holders and purchasers, joint tenants, or business partners. A person who suspects his or her property is the target of a criminal or administrative confiscation investigation may sell the property, give ownership to family members, or otherwise dispose of it.

Third-party claims on seized property are sometimes delayed in criminal confiscations because the claim often cannot be litigated until the end of the criminal trial. In an administrative confiscation, the procedure moves more quickly because the confiscation hearing usually occurs soon after the confiscation. In some jurisdictions, third parties are protected under the 'innocent owner' exception for non-conviction-based confiscations, if the government fails to establish that they had knowledge, consent, or wilful blindness to illegal usage of the property.

Disposition of confiscated assets

Some of most commonly confiscated assets are cash, cars and weapons, as well as luxury property such as boats, planes and jewellery. Residential and commercial property are also subject to confiscation. Once an asset is confiscated, it must be appraised to determine the property's value, less any claims against it. The item must be stored and maintained while ownership and any third-party claims are heard in court. If the challenge to the confiscation is not effective, the property is taken for government use or auctioned.

There has been controversy over the use of confiscated assets by some law enforcement agencies. Laws in some jurisdictions earmark specific uses for confiscated assets, such as for education costs. Some have claimed that confiscation of assets that are kept by police provide an incentive for spurious or aggressive confiscations (Bartels, 2010; Skolnick, 2008; Worrall and Kovandzic, 2008).

|

Country experiences in managing and disposing of confiscated assets In 2017, the UNODC released a publication titled "Effective Management and Disposal of Seized and Confiscated Assets" to provide States and relevant personnel with guidance on confiscation and seizure. Covering all geographical regions, varying legal systems, and differing levels of development, the study presents the experience of 64 countries on the management and disposal of seized and confiscated assets. The study presents previous experiences to help anyone tasked with developing legal and policy frameworks and/or responsible for the day-to-day management of seized and confiscated assets on knowing how to either avoid or better manage the associated risks and challenges (UNODC, 2017). FATF has also developed a list of recommendations and best practices on the management of frozen, seized and confiscated property (FATF, 2012). Ideally, an asset management framework has the following characteristics: (a) There is a framework for managing or overseeing the management of frozen, seized and confiscated property. This should include designated authority(ies) who are responsible for managing (or overseeing management of) such property. It should also include legal authority to preserve and manage such property. (b) There are sufficient resources in place to handle all aspects of asset management. (c) Appropriate planning takes place prior to taking freezing or seizing action. (d) There are measures in place to: (i) properly care for and preserve as far as practicable such property; (ii) deal with the individual's and third-party rights; (iii) dispose of confiscated property; (iv) keep appropriate records; and (v) take responsibility for any damages to be paid, following legal action by an individual in respect of loss or damage to property. (e) Those responsible for managing (or overseeing the management of) property have the capacity to provide immediate support and advice to law enforcement at all times in relation to freezing and seizure, including advising on and subsequently handling all practical issues in relation to freezing and seizure of property. (f) Those responsible for managing the property have sufficient expertise to manage any type of property. (g) There is statutory authority to permit a court to order a sale, including in cases where the property is perishable or rapidly depreciating. (h) There is a mechanism to permit the sale of property with the consent of the owner. (i) Property that is not suitable for public sale is destroyed. This includes any property: that is likely to be used for carrying out further criminal activity; for which ownership constitutes a criminal offence; that is counterfeit; or that is a threat to public safety. (j) In the case of confiscated property, there are mechanisms to transfer title, as necessary, without undue complication and delay. (k) To ensure the transparency and assess the effectiveness of the system, there are mechanisms to: track frozen/seized property; assess its value at the time of freezing/seizure, and thereafter as appropriate; keep records of its ultimate disposition; and, in the case of a sale, keep records of the value realised. |