This module is a resource for lecturers

Criminal gangs

Criminal gangs are a specific category of a criminal group closely linked to firearms. There is no specific definition of criminal gang and the concept, as will be seen later, tends to be fluid and to gradually merge in some cases into the broader concept of organized criminal group (OCG).

The label “gang” covers organizations ranging from highly sophisticated, well-organized national groups with links to other similar international groups at one end of the spectrum to more short-lived, sporadic and disorganized groups at the other. In terms of national classification, there is some disparity with the larger groups – the Hells Angels, for example, are regarded as a criminal organization in Canada following the Bonner & Lindsay case but have no specific criminal designation in many other countries.

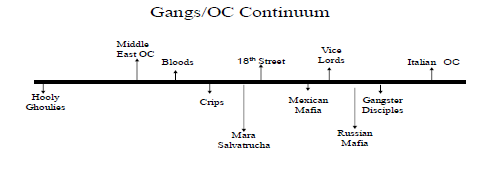

The distinctive line between these gangs and OCGs is not very clear as several gangs fit the definition of organized criminal group under UNTOC article 2, and the larger groups would also meet the transnational requirements of UNTOC article 3. As further explained below, the dividing line between a simple gang and an organized criminal group often depends on the different level of sophistication, politicization and internationalization.

The US National Institute of Justice (2011: 1) states that “gun-related homicide is most prevalent among gangs and during the commission of felony crimes” and 92% of gang-related homicides related to guns in 2008.

In Central America’s so-called Northern Triangle of El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras, street gangs, or ‘maras’, helped to drive murder rates in these countries to highs unmatched elsewhere in the world (International Crisis Group, 2017).

Reporting on Asia, Palasinski et al. (2016: 142-143) note how “gang-related crime in China has become more serious and violent in the recent years” and “youth gangs appear to be increasing their involvement in drug trafficking in India.”

In Africa, gang violence is also increasingly a growing problem. The National Cohesion and Integration Committee (NCIC, 2018) reveals a proliferation of organized gangs in Kenya, for example, in which gang membership frequently transcends traditional boundaries of gender and age based on young men to include women and pre-teenage children.

Concepts and terms

Unlike OCGs, there is no specific internationally agreed definition of what comprises a “gang” and this does lead to some confusion in terminology. Although most gangs have “three or more members” and commit multiple “serious criminal offences”, they do not always have “defined roles”, “continuity of membership” or “a developed structure” identifiable in OCGs (UNODC, 2004).

Taking into consideration the use of terms in article 2 of UNTOC , gangs can be considered organized criminal groups or structured groups on a case to case basis, depending on the level of organization of each gang. The website of the US-based National Gang Investigators Association (NAGIA) proposes the following definition:

Some States do have a legislative definition of a gang, for example:

- In the UK, Section 51 of the Serious Crime Act 2015 inserts a revised definition of “gang” into the Policing and Crime Act 2009 (Section 34), which states that “something is “gang-related” if it occurs in the course of, or is otherwise related to, the activities of a group that

- consists of at least three people, and

- has one or more characteristics that enable its members to be identified by others as a group.

- In India, armed gangs of robbers are referred to as “dacoits” and Section 391 of the Indian Penal Code defines dacoity as:

“When five or more persons conjointly commit or attempt to commit a robbery, or where the whole number of persons conjointly committing or attempting to commit a robbery, and persons present and aiding such commission or attempt, amount to five or more, every person so committing, attempting or aiding, is said to commit dacoity.”

The FBI’s Gang Threat Assessment Report of 2011 distinguishes five basic types of gangs each with distinct characteristics, as shown in Figure 7.1 below:

Gang definitions

|

Gang |

Definition |

|

Street |

Street gangs are criminal organizations formed on the street operating throughout a national territory. |

|

Prison |

Prison gangs are criminal organizations that originated within the penal system and operate within correctional facilities, although released members may be operating on the street. Prison gangs are also self-perpetuating criminal entities that can continue their criminal operations outside the confines of the penal system. |

|

Outlaw Motorcycle (OMGs) |

OMGs are organizations whose members use their motorcycle clubs as conduits for criminal enterprises. |

|

One Percenter OMGs |

One Percenters are defined by Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) as any group of motorcyclists who have voluntarily made a commitment to band together to abide by their organization’s rules enforced by violence and who engage in activities that bring them and their club into repeated and serious conflict with society and the law. The group must be an ongoing organization, association of three (3) or more persons which have a common interest and/or activity characterized by the commission of or involvement in a pattern of criminal or delinquent conduct. ATF estimates there are approximately 300 One Percenter OMGs in the United States. |

|

Neighbourhood/Local |

Neighbourhood or local street gangs are confined to specific neighbourhoods and jurisdictions and often imitate larger, more powerful national gangs. The primary purpose for many neighbourhood gangs is drug distribution and sales. |

Figure 7.1 Adapted from the National Gang Intelligence Center (2011: 7-8)

The FBI Gang Threat Assessment identified around 33,000 violent street gangs, motorcycle gangs, and prison gangs with about 1.4 million criminally active members in the United States whose numbers have remained more or less constant in subsequent years. Many of these gangs are sophisticated and well organized; all use violence to control neighbourhoods and boost their illegal money-making activities, which include robbery, drug and firearms trafficking, prostitution and human trafficking, and fraud. Many gang members continue to commit crimes even after being sent to jail.

It is clear that parts of these definitions are similar to the UNTOC definition of an OCG, underlining the blurred distinction between the two types of groups.

Figure 7.2 The Blurred Division between Gangs and OCGs

As will be seen in the example of Central American gangs, the problem of street gangs is often closely linked with more complex and deep rooted problems of social exclusion, marginalization, and lack of education, social services and job opportunities. These issues call for more comprehensive social and crime prevention responses. The Small Arms Survey (2010: 86) warns that:

“…. policy-makers should aim to understand the broad nature and characteristics of these gangs and armed groups while also identifying the features specific to the given gang or armed group of interest. Only by developing a coherent and detailed picture of the particular gang (or armed group) — who they are, whom they represent, their origins, how they function, what they aim to achieve, and why members join — can policy-makers develop strategies to address the factors that enable and encourage their organization and mobilization and reduce their negative impacts on society.”

Demand for firearms

Gangs use firearms in much the same way, and for much the same reasons as OCGs, but predominantly for self-use. The 2007 article on the impact of gang formation on local patterns of crime suggests that there is a difference between gangs in the United States and those elsewhere, notably that “Gangs outside of the U.S. commit far fewer violent acts, especially lethally violent acts. The activities of these groups tend to include instrumental crimes related to drug dealing and robbery/theft” (Tita, George & Ridgeway, Greg., 2007: 208-237).

In general, gangs are not commonly related with “big business” firearms traffickers to have access to continuous flows of large and various firearms inventories. Gang firearms are usually procured at low scale, most of them being pistols and revolvers, sometimes shotguns and semi-automatic submachine guns but rarely assault rifles. In absence of continuous contacts with firearms traffickers, gang firearms are supplied through alternative methods such as theft, cross-border purchases, cascading private sales, straw purchases, modification or reactivation of legally purchased non-lethal firearms, and lately using the Internet and darknet. For more information on the darknet and cyber-enabled crime, see the E4J University Module Series on Cybercrime.

In the United States, however, gangs tend to have a more widespread use of firearms. One of the major findings of the National Gang Threat Assessment (National Gang Intelligence Center, 2011: 10) was that: “Gang members are acquiring high-powered, military-style weapons and equipment which poses a significant threat because of the potential to engage in lethal encounters with law enforcement officers, rival gang members and civilians.” In several US jurisdictions, gang members are reported to be armed with military-style weapons, such as high-calibre semi-automatic rifles, semi-automatic variants of AK-47 assault rifles, grenades and body armour. The National Gang Threat Assessment Report (2011: 43) goes on to state:

“Gang members acquire firearms through a variety of means, including illegal purchases; straw purchases through surrogates or middle-men; thefts from individuals, vehicles, residences and commercial establishments; theft from law enforcement and military officials, from gang members with connections to military sources of supply, and from other gangs, according to multiple law enforcement and NGIC reporting … Gang members are becoming more sophisticated and methodical in their methods of acquiring and purchasing firearms. Gang members often acquire their firearms through theft or through a middleman, often making a weapons trace more difficult … Enlisted military personnel are also being utilized by gang members as a ready source for weapons.”

Another source of illegal firearms for gangs is from their connections with burglars who may or may not be gang members or gang-affiliated. Cook (2018: 370) states that “Even if burglars and thieves do not themselves use the stolen guns to commit violent crime, they may sell them into an underground market that is a source of guns to gang members or other violence-prone offenders. Alternatively, burglars dispose of guns the same way that they dispose of other stolen merchandise, throh fences, who in turn sell to whoever is interested in buying merchandise at a discounted price.”

As well as being a tool for crime, firearms represent a cultural object among many gang members. In a gang’s world, a firearm represents the reflection of one’s status. The type and model, and the number of weapons owned by a gang member will bring respect and fear inside a specific group that will come with status recognition. It is estimated that on average half of the members of a gang are in possession of at least one firearm (Bjerregaard and Lizotte, 1995: 40).

Aside from being a status symbol, gangs use firearms for reasons similar to other organized criminal groups. These include power gain and maintenance, facilitation and commission of offences, and, to a lesser extent, firearms are lucrative trading commodities with gang members being predominantly the buyers in firearms related transactions.

Firearms as tools for power

Unlike OCGs, which have perhaps moved beyond an exclusive focus on territorial control, most gang violence is directed at other gangs in an attempt to gain and control territory (Howell, 2010). Since most gang violence is directed at other gangs, an additional justification for firearms possession is protection against rival gang attacks, especially with gang turf wars increasing internationally, as the case studies below show.

It is estimated that “24% of gang members own guns for protection, while only about 7% of non-gang members do so” (Bjerregaard and Lizotte, 1995: 46) and a more recent US National Institute of Justice (2006: 11) paper, which focused on Atlanta, USA, found that 29% of male gang members and 75% of female gang members who carried a gun did so because it made them feel safer. The percentages change to 42% and 39% respectively when gang members were asked if carrying a gun made them feel more powerful.

Firearms as crime enablers

Gangs accumulate capital from classic criminal activities, mostly performed at street level. Racketeering and extortion, debt-collection, robbery and assaults, gambling, drug trafficking, and prostitution, and to some extent firearms trafficking, are just a few of the criminal activities that involve gang members. Although gang members rarely use firearms physically against citizens, the possession of a firearm is associated with a resistance deterrent, and a tool to facilitate the commission of crimes. The situation changes when the criminal activities are against members of rival gangs. Murders, attempted murders, and armed assaults are accomplished with the effective use of a firearm.

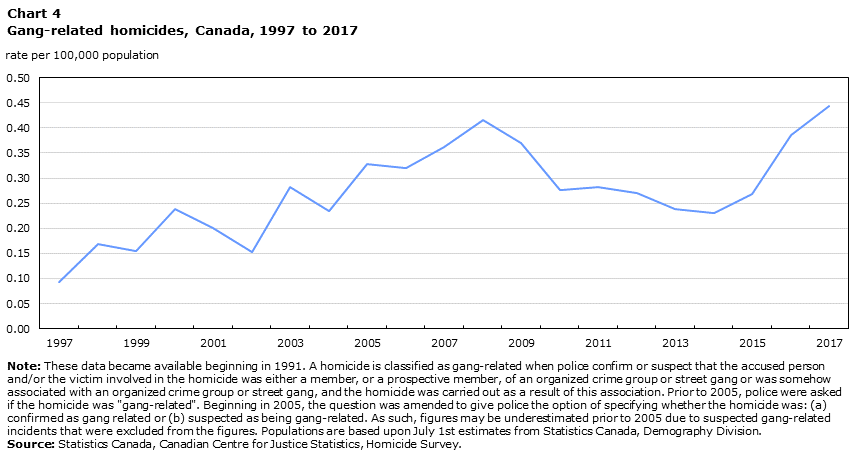

Gang-related crimes committed with a firearm have a huge impact on a country’s homicide rate as seen, for example, in Canada where the rise in number of street gangs has severely impacted on the country’s homicide rate. While methods of committing homicide in Canada have varied between knives and firearms over the years, a report on homicides in Canada in 2017 (Beattie et al., 2018) revealed that the majority of homicides related to shooting in the two years up to the release of the report. In fact, after a peak in 2008 followed by a drop in rates for several years, Canada’s firearm-related homicides have been increasing since 2014 primarily driven by gang-related violence (see Figure 7.3 below). In 2015, gang-related homicides committed with a firearm represented 12% of all homicides. In 2017, these accounted for 21%.

Compared to other types of homicide, gang-related homicides more often involve guns. According to Statistics Canada, 2017, almost nine in ten (87%) of gang-related homicides in Canada were committed with a firearm (137 victims), usually a handgun, compared to 27% for homicides that were not related to gang activity (129 victims) (Beattie et al., 2018).

Figure 7.3 Gang-related homicides in Canada from 1997 to 2017 (Beattie et al., 2018).

Similarly in the United States, the FBI highlights 34 jurisdictions in which law enforcement agencies report the majority of crimes being committed with a firearm. One issue of concern is gang infiltration of the military, where gang members of at least 53 different gangs were identified within domestic and international military installations. The potential criminal threat that this situation poses is considerable, particularly when advanced weaponry skills and combat techniques learned by gang members in the military services can then be employed on the streets when they return to civilian life (National Gang Intelligence Center, 2011).

Firearms as trafficking commodities

Most of the evidence reported above suggests that certainly at street-gang level, gangs are net buyers of firearms, and will use crime gained capital or trade other commodities or services to acquire them. There is not much evidence that low level gangs are also actively engaging in supplying weapons to other groups or individuals as a primary source of activity. There may be some situations where gangs are involved in small-scale trafficking, but most of the time the firearms are trafficked for the internal use of the gang.

From gangs to organized criminal groups

Noting that “most if not all organized criminal groups evolved….from their beginnings as a street gang”, there is a ‘natural transition’ of gangs into OCGs with the growing age and maturity of its members. The evolving line between criminal gangs and OCGs is often determined by the development of gangs from first to second or third generation, depending on their level of sophistication, politicization and internationalization(Smith et al., 2013: 6).

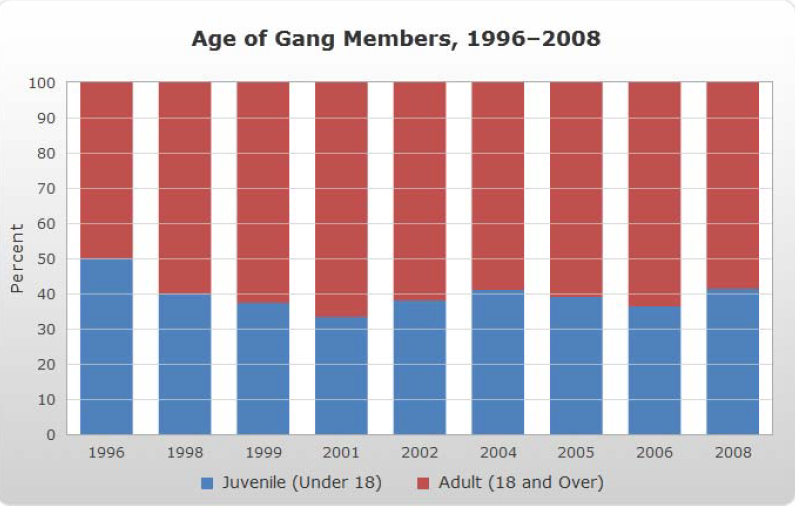

Traditional street gangs are usually considered first generation gangs, less structured and more typically engaged in turf wars with a localized focus. Second generation gangs tend to have a more organized structure, operate as a business with a strong market orientation. These gangs usually operate in a broader geographical area and have a more centralized and developed leadership. Third generation gangs are highly organized and sophisticated criminal organizations, with the goals of political power or financial acquisition, and tend to operate in a global environment. As Figure 7.4 illustrates, for every year, the number of adults involved in the gangs becomes greater than the number of juveniles, which would indicate that many gang members probably become the shot callers rather than the workers.

Figure 7.4 Age group of gang members in the United States, 1996-2008 (Smith et al., 2013)

The continuum between gangs evolving into organized criminal groups is shown in Figure 7.5 below and the case studies that follow provide additional evidence of this continuum:

Figure 7.5 Gangs/Organized Crime Continuum (Smith et al., 2013)

Case Studies

Australia

In 2018 the Supreme Court of New South Wales in Australia decided the case of Commissioner of Police v Bowtell (No. 2) [2018] NSWSC 520, which involved a turf war between rival members of the Nomads and the Finks, two Outlaw Motor Cycle Gangs (OMCGs or OMGs in other countries). A Serious Crime Prevention Order was imposed which forbids the defendants from associating with other members of their respective gangs for twelve months. The evidence in the case shows that a series of what police believed to be retaliatory shootings at property and individuals took place, with “20 rounds of .223 military grade ammunition” being fired into the premises (Supreme Court of New South Wales, 2018 Para 10).

ABC News reported in 2016 that “rural gun owners are being targeted by thieves, with the stolen weapons being channelled into the hands of outlaw motorcycle gangs in the Gold Coast and Brisbane” (Willacy, 2016: 1). This echoes the point made by Cook (2018) in relation to US gangs.

Central America

In the Northern Triangle region of Central America (NTCA), urban street gangs, or ‘maras’, emerging from civil wars and boosted by mass deportations from the US, have "mutated from youth groups defending their neighbourhoods’ turf in the 1980s to highly organized, hierarchical organizations that coerce, threaten and kill…” They contribute to the world’s highest homicide rates mostly ascribed to confrontations with the police, rivalries, score settling and intimidation (International Crisis Group, 2017: 1).

The two largest and notorious groups are the Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13) and the Barrio 18, or Eighteenth Street Gang (B18), both originating in the suburbs of Los Angeles in the early 1980s when young El Salvadorians banded together to protect themselves from other street gangs. From there, the maras took up their characteristic subcultural features to identify themselves, such as tattoos, clothing, language, and engaged in turf wars, petty drug trafficking and other criminal activities (International Crisis Group, 2017: 11).

Following more restrictive US immigration laws in the 1990s, more than 60,450 NTCA nationals were deported to the NTCA. Faced with stigmatization, social exclusion and limited access to education, social services and jobs, many of these young ‘mareros’ banded together reproducing the same names and gang structures of their US-based homologues, displacing or absorbing the local pandillas. As International Crisis Group (2017: 12) points out, “The maras that emerged were better organized, engaged in more violent crimes, used heavier weapons and proved more alluring than the many smaller pre-existing street gangs or pandillas. The latter were mostly reintegrated either into the B-18 or M-13.”

Maras are territorial gangs. Their major activity, source of income and territorial presence are derived from extortion, protection rackets and lesser drug trafficking activities, along with violence against women, and some engagement in human trafficking. Although not apparently directly engaged in larger international trafficking activities, their mutual cross-border links in the Northern Triangle region, access to weapons, and reported links to larger drugs, arms and human trafficking organizations operating in the region, fuelled by extreme levels of violence, assimilate them more with organized criminal groups rather than local youth gangs.

Rather than reducing the levels of violence, attempts to address the groups’ activities through repressive measures and zero tolerance approaches involving indiscriminate arrests and prolonged detentions in high security centres, only served to transform the maras into a more sophisticated criminal organization. This transformation unleashed an even greater spiral of violence in the region. Efforts to negotiate a truce with the maras in El Salvador failed, partly due to the lack of transparency and support from local communities.

The phenomenon of maras must be seen, however, in an historical and sociological perspective. According to the International Crisis Group (2017: 1), maras are not typical profit-seeking criminal organizations, but a deeply rooted social problem, “the product of mass deportation, family breakdown and institutional weaknesses in countries that fail to distribute adequately the wealth they produce among their citizens.” Armed violence reduction and prevention programmes combined with measures to reduce access to deadly weapons must be integral to wider strategies aimed at addressing the root causes of this complex problem.

South America

Primero Comando do Capital (PCC), a Brazilian criminal gang, formed in Taubaté Prison, São Paolo in 1993. After a number of years as a prison gang, the group morphed to occupy the shady zone between street gang and fully-fledged OCG (InSight Crime, 2018). Regarded as the most powerful gang in Brazil, the group has de facto control over much of the favela area in São Paolo and Rio de Janeiro. However, in 2017, the 20-year alliance between PCC and the Comando Vermelho of Rio ended with 21 homicides (Martín, 2017).

In 2014, a further sign of PCC’s development from a prison gang is evident in its attempt to develop a political wing and enter mainstream politics as well as extend its range of influence into Bolivia (Parkinson, 2013). That did not mean it was moving away from its criminal roots, however, when in 2018 newspapers reported São Paulo police suspicions of plans by PCC members to attack the country’s courthouses to steal firearms held by the court (Pagnan, 2018).

Europe

In 2018, London saw a surge in gang violence and firearms related murder with more than 50 murders reported in the first four months of the year, and at least seven of these the result of gunshot wounds. Member of Parliament David Lammy said many of the deaths result from fighting between rival gangs over the £11bn narcotics trade, of which London is central (British Broadcasting Corporation, 2018). This suggests that gangs in London are concerned with territory and market, which seems to align them more with OCGs (Hobbs, 1998). There have been active interventions by the Mayor of London (2019) into gang-related activity in London, but these are not consistent across the different London Boroughs.

In Naples, Italy, ‘baby gangs’ with leaders not older than 11-16 years, are involved in a bloody turf war with street attacks in the city and surrounding areas. Their favourite technique for asserting dominance is the "stesa", which is when they burst into a crowded square riding mopeds and firing shots at random (The Economist, 2017).

The new ‘baby-gang’ generation, which is challenging the supremacy of older, established Camorra families, bring generational change – abandoning omertă, the traditional code of silence, in favour of publicizing their exploits on social media (Tondo, 2019). Italian judge Nicola Quatrano refers to this new generation as “Baby Camorra”, who no longer follow the stereotypical role models portrayed in films such as ‘The Godfather’, instead preferring to “take fashion tips from Islamic extremists, with a number of their members wearing full beards reminiscent of the Taliban ones” (Galardini, 2016: 1). Quatrano also notes how they use similar tactics of embracing a “cult of death” in order to give some sort of meaning to their lives.

In September 2016, Quatrano sentenced 43 mafia criminals to prison for a variety of serious crimes, including murders and raids in the centre of Naples with the aim of spreading terror among the inhabitants to prevent them reporting the gang’s crimes to the police (Galardini, 2016). A prominent example was Emanuele Sibillo, a Camorra gangster. He grew up in the deprived Forcella area of Naples and became one of the most charismatic and feared young clan leaders. Having started his criminal career at a very young age, his first arrest came at the age of 15 when he was caught in possession of two Beretta 9mm pistols. Two years later, aged 17, he became leader of the baby-gang ES17, and was shot dead at the age of 19 during a turf war with a rival clan.

However, not all “baby gangs” necessarily have ties to organized crime. According to the State Attorney for juveniles in Naples, Maria de Luzenberger, in the past year authorities have become aware not only of teenage mafiosi but also of “very young kids who commit violence, apparently for no reason, simply to assert themselves and their presence, to mark their territory … It’s a grave social emergency as well as a criminal emergency.” Luzenberger linked the problem to a lack of social services, especially in the outskirts of Naples (The Local, 2018).

These examples are all attributable to organizations referred to as gangs, but all illustrate the blurred division between gangs and OCGs.

Next: Terrorist groups

Next: Terrorist groups

Back to top

Back to top