This module is a resource for lecturers

Indirect impacts of firearms on states or communities

The impact of firearms is most readily seen in conflicts and crime by the magnitude of homicides and other violent deaths as indicated above. However, there are consequences less visible and therefore harder to measure and often longer lasting that need understanding in order to prevent, reduce and eliminate the violence associated with firearms. This Module uses frequently the term 'weaponization' to refer to the broader impact of firearms on societies, and which describes a situation where firearms are easily accessible within a State or community, or readily available to those who would kill, injure, or intimidate others for political or criminal purposes.

Firearms and development

Most of the campaigns to reduce armed violence, leading up to the adoption of international instruments such as the Firearms Protocol and the Programme of Action on Small Arms (PoA) in 2001, and the Arms Trade Treaty in 2014 (United Nations, 2014), shared the common concern for the human suffering associated with the availability and misuse of firearms, and with their broader impact on development and on society. This is when ad hoc data and studies were first generated on the effects of armed violence on economic, social, political and human development. The Small Arms Survey 2003: Development Denied (see also Batchelor and Krause, 2003),presented an analysis of the links between armed violence and human development in greater depth. Table 1.3 provides an overview on the most visible direct and indirect effects of conflict or crime-related violence on a State or community.

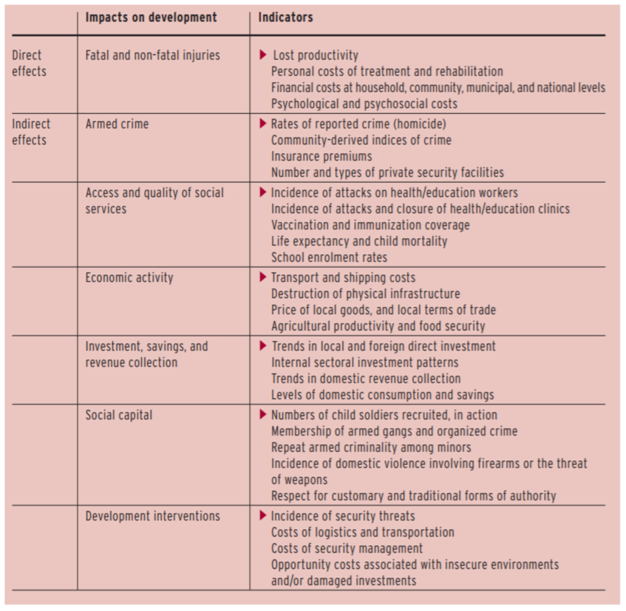

Table 1.3 - The effects of small arms misuse on human development (Source: Small Arms Survey 2003: Chapter 4: 131)

Since then, research in this field has developed considerably, especially in connection with the Millenium Development Goals and more recently with the new 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, but the above overview of impact on development and relevant indicators remains a valid starting point for an introduction to the effects associated with the acqusition, transfer and accumulation of firearms in communities and societies. While some of these effects are self-explanatory, others need further explanation. A number of these issues are considered in more depth in Module 10.

Firearms and human rights

The relationship between firearms and human rights is complex. Whilst firearms play a critical role in law enforcement and military operations for the protection of human rights and security, they are also often used to violate human rights.

In 2015, the Human Rights Council, requested the High Commissioner of Human Rights to prepare a report on the different ways in which civilian acquisition, possession and use of firearms have been effectively regulated. The purpose was to assess the contribution such regulations make to the protection of human rights, in particular the right to life and security of a person, and to identify the best practices that may guide States to further develop relevant national regulations (Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, 2016). The report was developed with contributions from States, United Nations agencies, international organizations, national human rights institutions, and non-governmental organizations and based on a standard questionnaire and published in 2016. The report concluded that:

- It is widely recognized that firearms are the main tool used to commit acts of violence and crime.

- The Secretariat of the Geneva Declaration on Armed Violence and Development has found that at least 754,000 individuals are victims of non-fatal firearms injuries every year.

- Other negative and long-term consequences of firearms that are less documented include non-physical harm such as psychological trauma and stress from being threatened or observing firearm violence.

- Many States agreed that firearms were "the primary medium" of human rights violations and abuses and that violence was often encouraged by the ready availability and abundance of firearms.

Illicit firearms trafficking and violence negatively impacts on security and on development, and thus can directly threaten the achievement of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, in particular its SDG 16, namely to promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels. However, the question of the relationship between firearms and human rights is more complex and often subject to debate.

These sometimes polarized views can be exemplified by looking at the positions of two well known NGOs active in this field. On the one hand, is the position taken by Amnesty International in their website 'Gun Violence - Key facts' in which they argue that gun violence infringes the rights to life, personal security and freedom of expression among other things.

On the other hand, there are lobbyists and campaign groups, such as the United States National Rifle Association (NRA), that consider keeping and bearing a gun should be seen as a constitutional right based on the Second Amendment of US constitution, and claim their right to self-defence as a basic human right. Nevertheless, the controversial position of the NRA has been the subject of multiple debates regarding who are the real defenders of Second Amendment and the role NRA had in shaping firearms legislation (Erickson, 2018). The debates, largely confined to the United States, question whether the right to self-defence as a constitutional right automatically elevates it to the level of a fundamental human right. The complexity of this debate involves broader questions on the State 's monopoly (and obligation) to legally use force and firearms to protect its citizens versus the right of citizens to own and use weapons for self-defence purposes, and to 'take justice in their hands' (Brettschneider, 2018). These issues lie outside the scope of this Module series and therefore cannot be fully addressed here.

Regardless of the above, there is general acceptance of the obligation of all States to adopt national legislation and measures as may be necessary to regulate and control firearms, and the use of armed force including the use of firearms by police forces, in line with and in full respect of international human rights instruments and standards.

Firearms, gender and youth

The issue of firearms trafficking and misuse has different facets and angles, and also has an important gender perspective. One of these aspects relates to how firearms related violence impacts on gender.

Homicides, including homicides with firearms, affect men and women differently. According to the UNODC Global Homicide Study, "there is a regional and gender bias towards male victims in homicide related to organized crime and gangs, but interpersonal homicide in the form of intimate partner/family-related homicide is far more evenly distributed across regions and is, on average, remarkably stable at the global level" (UNODC, 2013: 13).

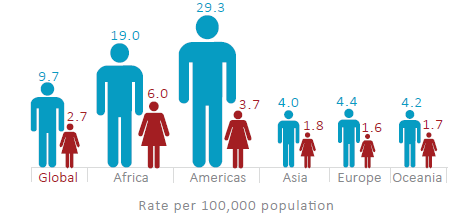

Figure 1.8 below shows rates of homicides with male and female victims by region:

Figure 1.8 Homicide rates, by region and by sex (2012 or latest year) (Source: UNODC, 2013: 28)

According to the UNODC Study, firearms are used against women less than men. On average, less than one-third of homicides with female victims are committed with firearms. Firearms are frequently displayed as a means to intimidate, threaten, or coerce women. However, women are disproportionally affected by intimate partner/family-related homicide than men: two thirds of victims globally are female (43,600 in 2012) and one third (20,000) are male. Almost half (47 per cent) of all female victims of homicide in 2012 were killed by their intimate partners or family members, compared to less than 6 per cent of male homicide victims. Consequently, the presence of firearms at home may increase the risk that domestic violence escalates into homicide, or that firearms are used to commit suicide. For further reading, please see Module 9 "Violence against Women " of the University Series on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice and the UNODC Global Study on Homicide - Gender-related killing of women and girls (UNODC, 2018).

Homicide also disproportionally affects youth. Globally, 15-29 and 30-44 age groups account for the vast majority of homicides. In South America and Central America, the homicide rate for male victims aged 15-29 is more than four times the global average rate for that age group. According to the 2013 UNODC Global Homicide Study, more than half of all global homicides victims are under 30 years of age.

Impacts on health care facilities and workers

An often underestimated dimension of the impact of armed violence relates to health care facilities, as well as on the staff working in health care. Around the globe, armed violence creates more emergency situations, and necessitates the deployment of health workers into areas affected by elevated levels of firearms violence. One clear effect of high levels of firearms violence on health care systems is their increased costs, as more human and financial resources are required to face the medical emergencies, and the longer-term effects may result in a deterioration of the country's health system as a whole. Developing countries with less robust health care systems are particularly exposed to the risk of seeing their system collapse as a result of sudden increases of armed violence.

The effect of firearms violence on the health workers is, however, more complex. These workers face many challenges, including overwhelming demands, insufficient resources, ongoing insecurity, lack of training, supplies and medicines, heightened anxiety and fear on the part of patients and families, limited access, bureaucratic hurdles, stress and exhaustion. Bergen and Fisher (2003) refer to the emotional impact of traumatic events on healthcare workers as 'secondary trauma', which plays a significant role in the physical and mental health of staff. For those who work in regions where firearms injuries are relatively rare, mass shootings such as the Paris attacks require medical staff to adopt practices akin to those working in military conflict, but without necessarily having the appropriate training. This places huge pressures on health care professionals (CBC News, 2015).

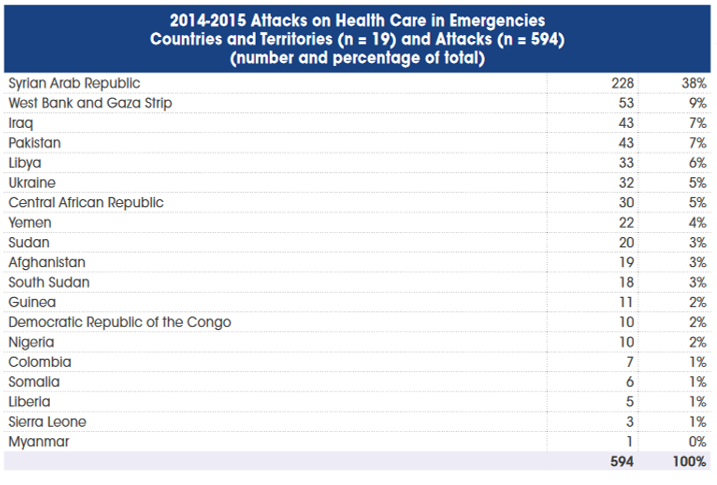

Table 1.5 Number of reported attacks on health care in emergencies in 2014 and 2015 (Source: World Health Organization, 2016: 4)

Primary trauma (Bergen and Fisher, 2003) occurs when healthcare workers are themselves the victims of violent attacks. In a World Health Organization (WHO) report, data was gathered on attacks, which were defined as "any act of verbal or physical violence or obstruction or threat of violence that interferes with the availability, access and delivery of curative and/or preventive health services during emergencies. Countries included in this report are those facing acute or protracted emergencies with health consequences resulting from any hazard" (WHO, 2016: 2). The WHO report suggests that in this two-year period, there were 959 deaths and 1,561 injuries from documented attacks against healthcare workers. The statistics do not differentiate on the type of attacks, whether committed with firearms or with other means, but it reveals a dimension of armed violence that is not always sufficiently visualized.

Impact of firearms on citizen's security

Domestic crime

The availability and criminal use of firearms has a clear impact on citizen's security. As seen before, firearms are an important enabler and aggravator for many forms of crime. The easy access and availability of firearms tend to increase the risks that interpersonal conflicts may degenerate to a lethal encounter in the presence of firearms. Domestic violence, property offences, and various minor conflicts tend to exacerbate and produce serious harm if at least one of the parties involved has access to a firearm. The use of firearms in interpersonal conflict settings will increase not only the severity of harm but also the number of victims when compared with situations where melee arms are involved.

It is no surprise that countries affected by high levels of crime and violence often face challenges of uncontrolled proliferation and trafficking in firearms, and that most of the firearms used in crimes happen to be of illicit origin. This means they were not used by their legitimate owners but had previously been lost or stolen, or illicitly trafficked and sold on the black market to criminal or terrorist groups.

Although many countries in the world have measures in place to control manufacture, secure stocks and regulate legal possession of firearms, their movement and transfer, weak normative frameworks and legislative gaps remain a major problem in many parts of the world (See Module 6: National Regulations on Firearms). Criminals will find it more or less difficult to gain access to firearms on the legal market depending on the legal framework in place and on its actual enforcement capacity. When seeking the acquisition of firearms in countries with strong regulatory regimes and good enforcement practices, criminals will most likely have to procure them through other illicit means. These include thefts (for example, from state entities, civilian households or private security companies), illicit manufacturing/conversion, or illicit trafficking from other countries with either lax laws on possession, uncontrolled surplus accumulations, or ineffective manufacturing control systems (See Module 4: Illicit Firearms Market).

The result is an increase in the circulation and use of illicitly acquired firearms in domestic crime, especially by gangs and other armed groups. In some countries the situation of uncontrolled proliferation and trafficking of firearms in societies can lead criminals to find more capable and lethal weapons at their disposal than the internal security forces of the community or State (See Module 7: Firearms, Terrorism and Organized Crime). The consequences of this 'weaponization' of societies can be deep and far reaching. One example of its long term impact is the increased presence in many countries of firearms in ordinary and domestic crimes traditionally not linked to firearms.

National crime statistics can provide a useful insight on the use of firearms in different crimes. At the global level, UNODC, through its Crime Trends Statistics (CTS), regularly collects data on crime from Member States, which includes information on the use of firearms in crime. However, data on this aspect of gun crime remains difficult to obtain and inconsistent across all global regions. Regional or sub-regional studies are difficult to find, precisely because of the general lack of comparable data in this field, often within the same sub-region.

The recent EU funded research report by the EFFECT (Examining Firearms and Forensics across Territories) Project determined that "currently, it is not possible to determine the true extent of gun enabled crime across Europe since 'gun enabled crime' is not an identified notifiable offence category, nor is it consistently defined in legislation. Countries do not consistently record the presence of a firearm when a crime has been committed/recorded" (Bowen and Poole, 2016: 3). (Module 11 will look deeper into firearms related research)

A recent study by Project SAFTE (Duquet and Goris, 2018) on the illicit gun markets and firarms acquisition of terrorist networks in Europe found data to support the fact that there is an increasing number of firearms in the illicit market in Europe, since Europe has fewer seizures of firearms than thefts of firearms. This increase in supply suggests that there are more weapons available to criminals and terrorists on the black market making it easier for them to acquire firearms. In these circumstances, it is reasonable to assume that this will fuel further demand, particuarly among gangs, as the requirement to own a firearm for defence against other gangs and rival criminals increases. This has the potential to result in an urban arms race, and subsequent increases in deaths and injuries ( Duquet and Goris, 2018).

Organized crime

Illicitly trafficked and acquired firearms and their criminal use are of great relevance to organized crime. Firearms represent the means to obtain, maintain and increase the power of these groups, as well as being facilitators for crime. They are also a lucrative trafficking commodity to be traded for other illicit goods, such as drugs, precious metals or looted or trafficked cultural heritage. Illicit trafficking is the quintessence of most organized crime activities, and firearms usually play a leading role in it.

Organized criminal groups need firearms to accomplish their goals of gaining and maintaining power and using that power to obtain wealth. The same concept applies to street gangs as much as organized criminal groups that control zones of influence at urban, regional, and even national levels. Gaining power means literally going to war with opponents seeking the same interests. In some urban areas, seen for example in Central America, gang members have easy access to illicit firearms coming from insecure stocks as well as trafficked into the region, often linked to the illicit drug trade in the region. Criminal organization members are frequently involved in, and connected to, a wide range of illicit networks of all kinds (drugs, extortion, human trafficking, etc.). Their demand for weapons is, in this respect, significant and relatively constant.

The effects of this demand can be seen globally with a direct impact on development. During a 2017 conference in Africa, officials declared that "Illicit arms intensify conflicts and facilitate organized crime. Even when they don't occur in tandem, arms trafficking abets crimes like drug trafficking, human trafficking, illegal mining, fishing, wildlife trade and oil theft" ( ENACT, 2017: 1). These issues are considered in more detail in Module 7: Firearms, Terrorism and Organized Crime, and fully within the E4J University Module Series on Organized Crime.

Terrorism

The illicit availability and access to weapons, including firearms, and their criminal use is of particular concern in terrorism where the use of firearms contributes to the increased threat and destructive power of these groups, and thus their impact on peace, security and safety of citizens.

A study by the Flemish Peace Institute (Duquet et al., 2019), "Armed to Kill ", indicates that terrorists in Europe have increased the use of firearms/SALW in conjunction with explosives and other devices. These findings are not exclusive to one region and are, in fact, confirmed by a recent study by Nuwer (2018) which shows that firearms are the tools that create the most fatalities in terrorist attacks (see also Bajekal and Walt, 2015).

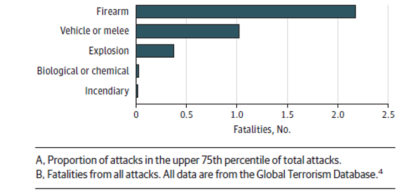

Several anecdotal cases from different regions in the world showcase how the use of firearms in terrorist attacks is on the rise. Many of the more recent terrorist attacks perpetrated over the past three years in African countries, such as Burkina Faso, Kenya, Mali, Niger and Nigeria, to mention a few, were perpetrated with firearms, in particular fully automatic rifles, and improvised explosive devices (IEDs). Similar trends have been found in countries less prone to terrorist attacks. A research letter published by JAMA Internal Medicine compares the proportion of terrorist attacks committed with firearms in the United States with the proportion in other high-income countries, as well as the deadliness of attacks with firearms compared to those by other means (Tessler, 2017). Of nearly 3,000 incidents in the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand between 2002 and 2016, 9.2% were committed with firearms. Nearly half were explosive attacks, and over one third used incendiary devices. Despite firearms being the modus operandi of less than 10% of the incidents, they accounted for over half of the fatalities at 566, or approximately 55% ( Tessler, 2017). Data on fatalities by mode of terrorist attacks are illustrated in Figure 1.9 below.

Figure 1.9 - Fatalities per attack by weapon used

The terrorist acts in Europe also reveal the growing importance of firearms for terrorists. This was the focus of the 2018 Project SAFTE report, which stated that in Europe, firearms from the illicit market are most frequently used by terrorists, but little is known about their acquisition and this reveals the bigger problem of scarcity of data on illicit firearms trafficking in Europe ( Duquet et al, 2018).

These issues are further considered in Module 7: Firearms, Terrorism and Organized Crime.

Growth of private security companies

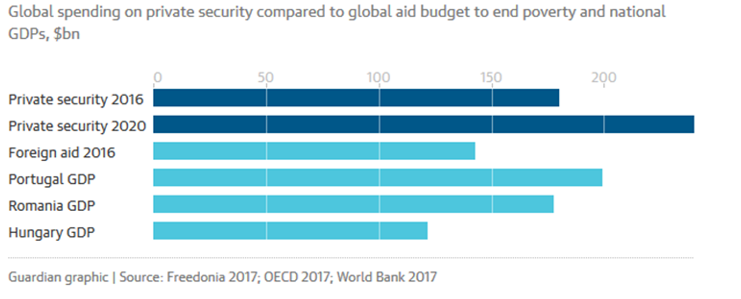

In many locations and regions around the world, more resources are spent on private security than on development. This is among other factors the result of the fear and violence determined by the misuse of firearms. Human security first and foremost means the freedom from fear. In regions where government security forces lack the capacity and/or the legitimacy to provide security, this vacuum is often filled by private security companies. Figure 1.10, taken from a report in The Guardian (Provost, 2017) in the UK, illustrates that the global spending on private security currently outstrips the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of a number of European countries, and is projected to grow to in excess of $200 billion by 2020.

Figure 1.10 'The industry of inequality: why the world is obsessed with private security' ( Provost, 2017: Source: Freedonia 2017; OECD 2017; World Bank 2017)

More than 40 countries - including the United States, China, Canada, Australia and the United Kingdom - have more workers hired to protect specific people, places and things than police officers with a mandate to protect the public at large, according to this data. In Britain, 232,000 private guards were employed in 2015, compared with 151,000 police. 'The global market for private security services, which include private guarding, surveillance and armed transport, is now worth an estimated $180bn (£140bn), and is projected to grow to $240bn by 2020 . This far outweighs the total international aid budget to end global poverty ( $140bn a year) - and the GDPs of more than 100 countries, including Hungary and Morocco' ( Provost, 2017: 1). This serves to further global inequalities, as those societies, communities and individuals that can afford to invest in private security contribute to a displacement of illicit activities to less secure communities and individuals.

Resorting to private security services is often also the result of high levels of crime and insecurity, and presence of organized criminal groups, which instill an increased sense of fear among communities, and a loss of confidence in the State's capacity to protect them. In several countries, self-defence groups have been established in past decades in response to the State 's perceived failure to protect its citizens or to exercise full control over its territory. If not properly regulated and controlled, private security companies or entities are at risk of themselves becoming involved in criminal activities. Some develop as parallel civic organizations and degenerate into criminal organizations, as has been the case for the Sicilian mafia, which in its origin was a loose organization of citizens looking to protect themselves in the absence of State efficacy in doing so:

"Sicilians banded together in groups to protect themselves [from a long line of foreign invaders] and carry out their own justice. In Sicily, the term 'mafioso', or Mafia member, initially had no criminal connotations and was used to refer to a person who was suspicious of central authority" ( History.com).

In other cases, self-defence groups were established by the State to respond to growing or imminent threats, such as the so-called 'Convivir' in Colombia, which were established in the 1994 by government decree to support rural communities of landowners in response to growing guerrilla activity and drug trafficking groups (ElTiempo). In a few years only, many of these groups started to commit abuses against civilians, engaged in counter-insurgency activities and developed close ties to local paramilitary groups ( Human Rights Watch). In 1997, the Constitutional Court of Colombia stated that CONVIVIR members could not gather intelligence information and could not employ military grade weapons. Other restrictions included increasing legal supervision, and in early 1998, dozens of former CONVIVIR groups had their licences revoked, because they did not turn in their weapons and withheld information about their personnel. As a result, many of these groups were dissolved and handed in their weapons, and many others joined existing paramilitary groups, such as the ' United Self-Defenders of Colombia' (Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia, or AUC).

Increased fear and insecurity caused by criminal groups can ultimately lead to increased levels of (forced) migration and internal displacement. One such example is Central America's violent northern triangle ( CFR).

Another potential impact of the rise in private security is the lowering of control over the acquisition of arms for companies. Often the State mechanisms to control such acquisitions and imports are non-existent, and companies make their own arrangements with suppliers. This results in a lack of accountability and these weapons may fall into illicit hands.

The growth of civilian private security services and the broadened scope of their activities in many countries require appropriate mechanisms for regulation and oversight to ensure compliance with national and international rules and regulations and prevent illicit actions. The regulation of private security companies is often non-existent, or insufficiently regulated by the State, with a risk of creating important legal loopholes and sources for illicit arms diversion. Regulations differ considerably ranging from total prohibition of such companies, as in Bolivia, to more or less regulated activities. In some countries, these companies cannot hold firearms, whereas in others it is permitted and the State issues licences for the employees of these companies to carry firearms.

There are currently no specific United Nations instruments, standards or norms addressing civilian private security services. However, the 'Introductory Handbook on State Regulation concerning Civilian Private Security Services and their Contribution to Crime Prevention and Community Safety' (UNODC, 2014a) identifies a wide range of international standards that are relevant and applicable to the security sector, and which can be used as a guiding tool to strengthen State regulation and control over private security companies. This is apparent, for example, in the standards relating to the State 's responsibility to prevent crime, protect human rights and govern the use of force, detention and arrest, as well as those relating to the relationship between the private sector and human rights and the protection of the rights of workers. The handbook recommends that sensitive issues, such as whether or not private security workers should have special powers or the right to carry weapons, should be made explicit and regulated as applicable by law, while the areas where private security entities are not expected to operate should be identified in the legislation. A licensing system for operatives and providers is recommended as the cornerstone of an effective regulatory system. Accepted best practice is for licensing to apply to both, so that standards can be raised both in companies and among individual licence holders, and should include licences for firearms to cover cases where companies are allowed to hold and carry them.

According to the UNODC study, experience shows that civilian private security services can provide States with a resource, which if properly regulated can contribute significantly to reducing crime and enhancing community safety, in particular through partnerships and information-sharing with the State police. Professional codes of conduct and legislation need to direct and control the sharing of information between public and private security actors (UNODC, 2014a).

Next:

International and national responses and approaches to addressing the problem of illicit trafficking and access of firearms

Next:

International and national responses and approaches to addressing the problem of illicit trafficking and access of firearms

Back to top

Back to top