Published in January 2022

This module is a resource for lecturers

Incentives to participate in illegal wildlife, logging and fishing economies

Local people are not just incentivised to engage with wildlife trafficking because of frustration or anger at the negative impacts they may face from conservation. They are also incentivised if the benefits they can gain from these acts outweigh any other benefits that they may obtain from conservation or alternative livelihoods. As an example, a single rhino hunt can earn a rhino poacher more than the average annual income of rural citizens in southern Africa (Hübschle 2016). Likewise, tiger pelt, bones and genitalia can fetch a small fortune for poachers in South Asia.

The question why individuals and communities participate in illegal wildlife, logging or fishing economies is important to help devise remedial responses. The poaching of endangered or threatened species is not a new phenomenon, but scholarly interest has focused on economic, thrill-seeking and opportunistic theories of poaching in the past (see for example Muth and Bowe 1998, Forsyth and Marckese 1993). Scholars from a variety of disciplines, including criminology, economics, anthropology, sociology, security studies, human geography and international relations have researched drivers of poaching behaviour, profiled the offenders, and categorized the crime (von Essen et al. 2014: 7).

Many scholars provide economic motivations for poaching decisions (Kahler and Gore 2012). A new stream of scholars has started to explore the socio-political context (Fischer et al. 2013), pervasive social and economic inequality (Lunstrum and Givá 2020), cultural explanations (Bell, Hampshire, and Topalidou 2007), and the institutional setting (Kahler and Gore 2012) to explain poaching decisions. When it comes to high-value species, the entry of transnational criminal networks, growing demand in consumer markets and high levels of poverty of people living close to protected areas are proffered as leading and interlinked drivers (see for example Milliken 2014, Montesh 2013).

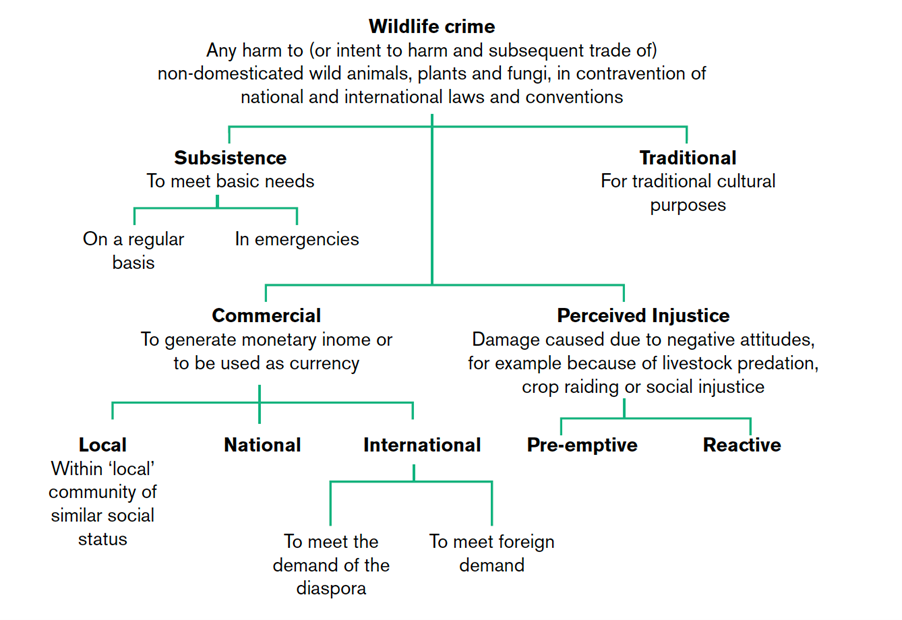

The relationship of IPLCs and protected areas is complex due to historical, social and political factors, which remain largely unacknowledged in the extant literature. Moreover, the underlying assumption that poverty leads to deviance has long been questioned in sociological and criminological research (Hirschi 1973, Merton 1938). A study undertaken in Uganda (Harrison et al. 2015) identified several factors that led to household involvement in wildlife crime (see Figure 3). These include basic needs (subsistence), generating income beyond basic needs (commercial poaching), responses to perceived injustice (human-wildlife conflict) and cultural traditions.

Figure 3 - A typology of factors driving wildlife crime in Uganda (Harrison et al., 2015:21)

Scholars have started to acknowledge the historical context of land expropriation, loss of natural resource use rights, contested illegality as well as the forced removals during colonial times to explain why IPLCs may support or engage in poaching economies in southern Africa (Hübschle, 2016; Hübschle, 2017; Hübschle & Shearing 2018; Moneron, Armstrong & Newton, 2020). Beyond poaching for the “cooking pot and pocket book” (Kahler and Gore 2012), convicted poachers in South Africa and Mozambique cited feelings of stress, disempowerment, anger, peer pressure and emasculation leading to poaching decisions. While younger poachers (late teens to late twenties) espoused anomic and individualistic desires, older offenders wanted to take care of their families and the community (Hübschle 2017). Some convicted wildlife offenders were set on achieving social upward mobility and saw illegal hunting as a means to an end to political leadership or wanted to provide social welfare to community members. Structural violence, the generational pain of dispossession and marginalization provide a facilitating milieu (Hübschle & Shearing 2018: 32), while unhappiness with rule-makers and the perceived illegitimacy of the rules (contested illegality) highlighted the distrust of past and present state authority. A study undertaken amongst convicted wildlife criminals in Namibia found that some were driven by curiosity as they were previously unaware of the species and wanted to find out more about it (Prinsloo, Riley-Smith, and Newton 2021).

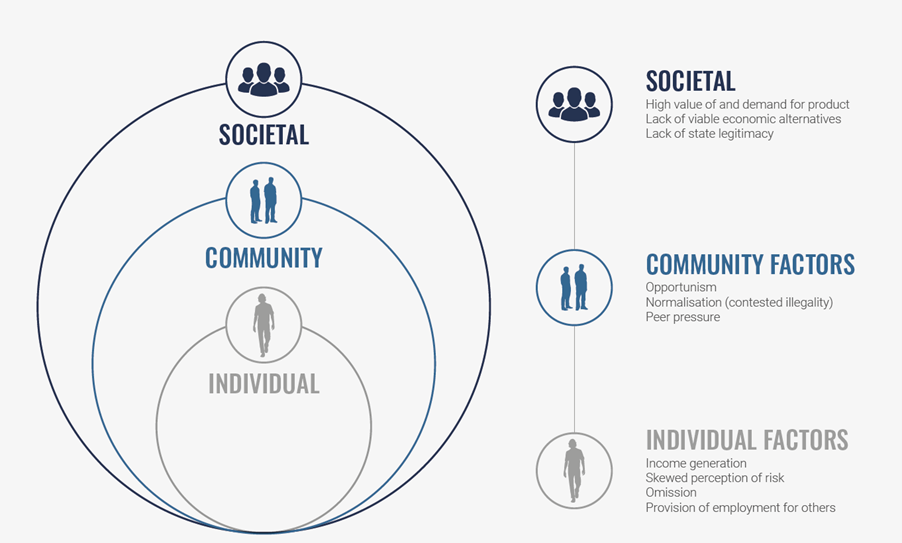

Moneron and colleagues (2020: 26) from the wildlife trade network TRAFFIC categorized influencing factors that led to the commission of wildlife offences among convicted wildlife criminals in South Africa into individual, community and societal factors. In addition to the earlier factors, the study identified a skewed perception of risk and the provision of employment to others as key individual drivers, while opportunism and peer pressure were added to the list of community drivers.

Figure 4 - Drivers of poaching (Moneron et al. (2020)

The previous section made reference to local people getting involved in poaching economies for reasons of social or political protest, including unhappiness with rule-makers or the perceived illegitimacy of the rules (see also the section on contested illegality). The following case study shows how perceptions of unfair and unjust resource distribution – in this case, fishing quotas – might lead to protest fishing, a form of illegal fishing.

Case study: Protest fishing by small-scale fishers in the Western Cape of South Africa

The Western Cape region in South Africa has a long history of artisanal (or small-scale) fishing, with more than 20 traditional fishing communities distributed between Ebenhaeser, at the mouth of the Olifants River on the west coast, and Arniston, 30 km east of Cape Agulhas. These fishing communities have been socially and economically marginalized by discriminatory race-based legislation since the apartheid era, with the unfortunate legacy continuing well into South Africa’s post-1994 democracy. While a single definition of ‘small-scale fishers’ has not been agreed upon, there is general consensus that the term refers to fishers who operate from or near the shore, using relatively inexpensive gear and technology, and target a variety of marine resources (FAO 2005). In South Africa, the term ‘small-scale fishing’ encompasses a wide spectrum of fishing activities, ranging from subsistence harvesting to running small commercial ventures.

The onset of industrial fishing at the turn of the 20th century had negative consequences for traditional fishers in the Western Cape, who began competing with emerging export fisheries for resources and labour (van Sittert et al. 2006). During that time, West Coast Rock Lobster (Jasus lalandii), known locally as kreef, went from being considered “poor man’s food” to a lucrative export commodity with the emergence of profitable new markets in Europe (Van Sittert 2003). Kreef, along with the aggressive predator snake mackerel species known as snoek (Thyrsites atun), formed the cornerstone of traditional Cape fishing practices.

Discriminatory apartheid legislation from the 1940s onwards made matters worse for fishers classified as “non-white” under apartheid’s race categories, systematically removing their rights to own land and property, denying them access to marine resources, and effectively reducing their role to providing labour for white-owned fishing companies (Sowman et al. 2011). Under the apartheid dispensation, the diverse group that constituted traditional fishers fell largely within the “coloured” racial category, a largely arbitrary designation for people of mixed heritage or distant native Khoi-San descent. Commercial fishing quotas were reserved for white people until the end of apartheid. At the same time, the policing of informal fishing was far less strict, and many small-scale fishers were able to fish for subsistence and informal commercial use.

This changed with the onset of the new quota system in the early 1990s. In 1998, the Marine Living Resources Act (MLRA) was passed, becoming the central piece of legislation controlling fisheries management in South Africa. The MLRA attempted a delicate balancing act, prioritizing transformation and social justice yet emphasizing the need to protect resources and maintain economic stability (van Sittert et al. 2006). The practical difficulty of achieving these three objectives in tandem has remained a central theme in South African fisheries and conservation management ever since.

Fisheries reform in South Africa was fraught with difficulties from the start. Flaws in the rights allocation process meant that many newcomers to the fishing industry received permits at the expense of legitimate fishers, creating a new “black” fishing elite without addressing existing problems of exclusion (Isaacs 2006). The issuing of short-term quotas, valid for just one year at a time, also discouraged investment by new rights holders, and many simply sold their rights back to white-owned companies for lucrative pay-outs (Kleinschmidt, Sauer, and Britz 2003). This made a small number of “paper quota” holders rich, but entirely negated the government’s broader goal of transformation. Meanwhile, the fisheries authority was overwhelmed by applications and unable to process them.

The state’s failure to translate the progressive goals of the MLRA into action weakened its legitimacy in the eyes of many fishers, and “protest fishing” – or openly fishing without valid permits as a form of political action – flourished as a result.

Growing dissatisfaction among excluded fishers culminated in a class-action suit against the Minister of the Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism in 2004, when Masifundise Development Trust, a small-scale fishing NGO, took the government to court for failing to execute its transformation mandate in the fishing sector. The Equality Court ruled in favour of the fishers in 2005, demanding that the South African government draft a new policy for managing the small-scale fishing sector and that they implement a system of interim relief measures, granting fishers temporary access to marine resources until such time as the policy was implemented. The new policy was formally adopted in June 2012. It emphasizes the importance of addressing historical imbalances in South African fisheries sector, prioritizing the unique needs of small-scale fishers for the first time. The process of awarding small-scale fishing rights in the Western Cape remains flawed, however, and the process is under review in 2021.

Small-scale fishers in the Western Cape represent a highly vulnerable group, burdened with a legacy of race-based exclusion from the social and economic mainstream, and dependent on marine resources that are both in broad decline due to overfishing and environmental factors, and more difficult to access due to complicated institutional arrangements. Cape traditional fishing communities are sites of high unemployment, widespread poverty, and limited access to alternative livelihood opportunities (Sowman et al. 2011). In this context, illicit fishing, particularly of high value resources like kreef and abalone, has increased on a massive scale, with many communities highly reliant on income from illicit fisheries (Hauck 2009; Isaacs 2011; Isaacs and Witbooi 2019)..

The following case study is based on an ongoing research project on the social economy of poaching, transnational flows of rhino horn and demand by Annette Hübschle, with a focus on the Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park. (Compare with (Hübschle 2016, Hübschle and Shearing 2018, 2021, Hübschle 2017)). South Africa lost close to 10,000 rhinos to poachers between 2011 and 2021 (Department of Environmental Affairs, 2021). Commentators attribute the poaching crisis to increasing demand for rhino horn in Southeast and East Asia, poverty and lack of economic alternatives (Price 2017). Indeed, poverty is often portrayed as key driver of biodiversity loss including wildlife poaching (Twinamatsiko et al. 2014) and scholars rely largely on an economic definition of poverty. Yet, the results of the research by Hübschle suggest that motivations to support illegal wildlife economies vary in communities living adjacent to protected areas in southern Africa and may well go beyond lack of economic alternatives – see box below.

Extended case study: The social economy of rhino poaching

Research undertaken in local communities living adjacent to and within the Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park (GLTP) in southern Africa (consisting of Gonarezhou National Park, Kruger National Park and Limpopo National Park) shows that an exploration of the root causes of poaching is essential to developing successful interventions at local community level. The need for fine-grained data and an understanding of culture and context is important. Communities living inside or on the edge of the GLTP are often portrayed as a homogeneous group of people that consists of poachers and villagers who benefit from rhino poaching. It is suggested that rural poverty, opportunity structures of living close to the park and greed are feeding the poaching crisis. While these factors constitute sufficient drivers of poaching, the root causes of poaching touch on the history of conservation, hunting rights and land ownership in southern Africa.

The effects of structural violence are visible in the village communities that live on the edge of protected areas but also on the periphery of society when it comes to social development, public service delivery and economic upliftment projects. The continued economic, political and social marginalization of these village communities has given rise to environmental and social justice concerns. While the rhino has a bounty on its horn that far outweighs the average annual income of a rural villager, poaching is not just about the price of the horn but also about claiming reparations for the loss of land, hunting and natural resource and land use rights, and demands for economic opportunities and agency to co-determine the future of village communities.

Generational trauma linked to the marginalization, displacement and dispossession have emerged as drivers of illegal wildlife hunting, pushing rural dwellers to become involved in the poaching economy, and likewise motivating communities to shield perpetrators from law enforcement agents. There may also be indirect benefits accruing from the provision of support services to poachers. There is the trickle-down effect, whereby profits made from poaching may benefit, to some degree, the community to which the poacher or wildlife trafficker belongs. It should therefore not come as a surprise that some poachers originate in communities living near protected areas and private reserves. Some locals provide support services to poachers, such as accommodation, food and drink, intelligence, traditional medicine, and tracking and transport. In return, rhino poachers and traffickers provide the communities with material assistance and money where the state, conservation authorities and society have often failed to assist.

Interviews conducted among affected communities show that they feel that conservationists and the state value the lives of wild animals more than those of rural black people. The notion that parks and the interests of foreign tourists are prioritized over those of rural communities was a recurring theme in interviews and focus groups in South Africa and Mozambique. The importance attributed to the rhino has taken on a symbolic meaning to some communities, whose concerns over land restitution, land-use rights and livelihood strategies are perceived to be lower on the state’s agenda than its duty to protect an endangered wild animal. Some community members feel strongly about the lack of bottom-up negotiation when it comes to resolving conflicts around land rights, resettlement and who benefits from resources and socio-economic development initiatives. Conflicts have risen over inequitable income distribution of benefits. Local political elites, including traditional leaders, chiefs and village head(wo)men, often act as intermediaries between communities and the authorities in rural southern Africa, negotiating political, economic, social and land restitution deals.

It is evident, according to research participants, that feelings of anger, disempowerment and marginalization are also factors that lead to rhino poaching. When asked about what motivated them to become poachers, most of the interviewed poachers cited feelings of shame at not being able to provide for their families (or at having to do so through illegal means), of emasculation, stress, disempowerment and anger.

It is against this backdrop that many rhino poachers and traffickers have emerged as self-styled social workers, who use rhino poaching for their own upward social and economic mobility. Or, in the words of a Mozambique-based kingpin, ‘We are using rhino horn to free ourselves.’ Some rhino poachers claim they are fulfilling functions akin to social welfare, community development and political leadership. Like latter-day Robin Hoods or social bandits, they see rhino horn as instrumental in achieving these altruistic goals in an environment where the state is failing to do so. Indeed, representatives of the state and traditional leaders fulfil ceremonial duties that are often heavily subsidized by resident kingpins and poachers. Although many rhino kingpins have a criminal past linked to a range of illegal markets and organized crime, others used to work in the police or nature conservation. Participants of the study portrayed their criminal careers in rhino poaching as legitimate livelihoods. Two Mozambican kingpins, for example, have constructed their identity around the notion of being ‘economic freedom fighters’, who struggle for the economic and environmental emancipation of their communities. Others have labelled themselves as business entrepreneurs, developers, community workers or retired hunters. These strategies of legitimizing their activities also include appropriating job labels from the wildlife industry. Rhino poachers regard themselves as ‘professional hunters’ or simply ‘hunters.’ The position of a hunter comes with status and prestige in village communities, where a young boy’s first hunt is a rite of passage.

There is also the perception among some park officials that villagers benefit in equal measures from rhino poaching, with wealth being redistributed among the needy through a form of social banditry carried out by the poachers as noted above. Yet not all are motivated by collective upliftment. One poacher in his mid-20s argued that, because he bore the risk alone during his poaching sorties in the Kruger National Park, he was not prepared to share his profits with the community. ‘It benefits me, I don’t give to the community,’ he said.

The role, functions and identities of kingpins and poachers are clearly complex and contingent on the local context. Although many poachers originate from local communities, others join hunting crews from communities elsewhere and sometimes even from abroad. Therefore, the level of social embeddedness of kingpins and poachers varies among the communities. Further, not all poachers are paid equally well. A generation gap can also be detected when it comes to motives for poaching. Whereas older poachers (i.e. those who 30 and over) were concerned about family and community well-being, younger poachers displayed more individualistic traits, seeking self-realization and accumulation. A teenage poacher cited the adage of ‘get rich young or die trying’ as the motif and inspiration of his generation of poachers. Although there are examples of women engaging in poaching and illegal harvesting of wildlife in southern Africa, limited evidence (two cases) of female rhino poachers were found. There were a few examples of women operating trafficking and trade rings in Mozambique, however.

Perceptions vary among communities as to whether their fortunes and livelihoods have improved from poaching. Many local communities appear to benefit; others less so, or only indirectly. Direct handouts often appear to be limited to some of the more generous kingpins, who throw a village party by slaughtering a few cows and providing traditional beer after returning from a successful poaching expedition to the Kruger National Park. Others, however, have constructed small roads, water wells, spaza shops (a small neighbourhood grocery) and shebeens (tavern), and occasionally some cattle are donated to provide meat to community members. Compared to the meagre livelihoods of village communities, kingpins and poachers have purchasing power, allowing them to buy greater volumes of goods and services, which indirectly benefits community members.

The influx of hard cash into some communities has also had negative consequences, including increased alcohol consumption, drug use and sex work. In short, some communities may benefit from the trickle-down effect, but this is not always the case. It is thus incorrect to assume that entire communities are complicit in or benefit from poaching. In fact, some community members reported that they feared ‘the outsiders’, while others were threatened to collaborate or told to turn a blind eye. Focus groups revealed that mothers and wives were deeply concerned about the poaching phenomenon, fearing for their children’s or husbands’ lives and the potential loss of a breadwinner should they be killed or arrested. Far from being supportive of poaching, women said that it had affected the social fabric of village life, mostly to the detriment of women and children.

The focus groups revealed that there was an awareness about the ceiling to the rhino horn fortunes: kingpins acknowledged the existential threat to rhinos through poaching and that they would have to seek new sources of income or return to their old ones once the rhinos were gone. By 2017, the returns from rhino poaching had started to decrease on the Mozambican side of the Park, where community members stated that poachers had squandered the rhino profits. The increasing militarization of responses to rhino poaching pits communities against park authorities, rangers and rhinos. Focus groups with community representatives showed that the deaths of fathers, husbands, sons and brothers had led to outright antagonism among community members towards the park management, especially Kruger officials.

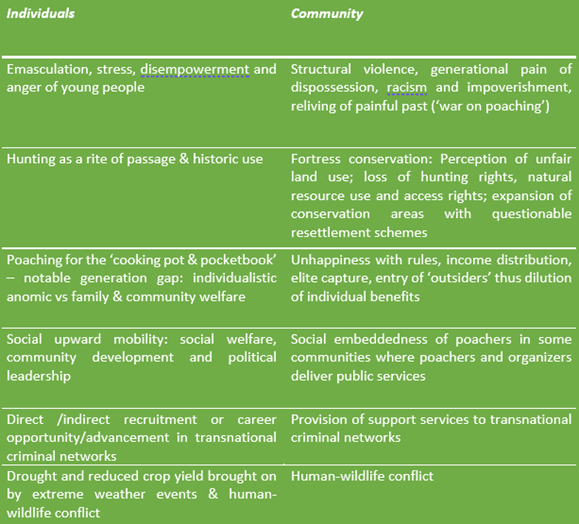

The table below shows individual and community motivations for poaching that emerged during this study. This study is by no means exhaustive. It is important to note that motivations are context-specific. Some of these motivations will be more or less relevant in different contexts thus requiring different solutions. Anyone wishing to implement projects on the ground ought to conduct a thorough assessment of the situation and ideally work with other agencies to avoid repeating work.

Table 1 - What motivates individuals to poach rhinos? Why do communities support illegal wildlife economies?

Next: Impact of enforcement-based approaches to wildlife trafficking on IPLCs

Next: Impact of enforcement-based approaches to wildlife trafficking on IPLCs

Back to top

Back to top