This module is a resource for lecturers

Topic three - Justice for children

With the near global ratification of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), the international community has agreed that legal safeguards are required to ensure that the distinct characteristics and rights of children are taken into account in all processes that affect children. In instances where children come into contact with justice systems (whether as victims, witnesses or alleged as, accused of or recognized as having infringed the penal law) international law requires that children be treated in a manner that is consistent with their human dignity, and which takes into account the specificities of their situation, and their age. There are further obligations on States parties to ensure that children are treated fairly, and in a manner that promotes their prospects for rehabilitation and reintegration. Key to this is the requirement that States parties implement specialized juvenile justice systems (laws, procedures, authorities and institutions) (CRC, 1990, article 40 (3)).

While neither the CRC nor the non-binding legal instruments on justice for children specify the kind of specialized juvenile justice system that should be implemented, the Committee on the Rights of the Child envisages that this encompasses specialized units within the police, the judiciary, the court system, the prosecution, probation services, and legal services (General Comment No. 10, 2007, paras 92-94; General Comment No. 24 2019, paras 105-110). The United Nations Model Strategies and Practical Measures on the Elimination of Violence against Children in the Field of Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice describe a specialized juvenile justice system as “one that takes into consideration the child’s right to protection, his or her individual needs, and his or her views in accordance with the age and maturity of the child”( UN, 2014, GA Resolution 69/194, para 6(d)).

United Nations standards and norms relevant to justice for children

The Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) is the only legally binding international instrument that imposes obligations on States parties to respect, protect and fulfil the specific human rights of children in all spheres of life (including in the context of justice).

In addition to the CRC, and General Comments No. 10 and No. 24, there is a wealth of material at the international level to guide the practical implementation of the specialized systems necessary to ensure children’s access to justice.

Relevant standards and norms include:

- UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Administration of Juvenile Justice (“The Beijing Rules”, 1985)

- UN Guidelines on the Prevention of Juvenile Delinquency (“The Riyadh Guidelines”, 1990),

- UN Rules for the Protection of Juveniles Deprived of their Liberty (“The Havana Rules”, 1990))

- UN Guidelines for Action on Children in the Criminal Justice System (“The Vienna Guidelines”, 1997)

- UN Guidelines on Justice in Matters involving Child Victims and Witnesses of Crime (ECOSOC Res 2005/20, 2005)

- UN Guidelines for the Appropriate Use and Conditions of Alternative Care for Children (GA Res 64/142, 2009)

- UN Model Strategies and Practical Measures on the Elimination of Violence against Children in the Field of Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice (UN, 2014, A/RES/69/194)

Further authoritative guidance is provided in: Guidance Note of the Secretary-General: UN Approach to Justice for Children (United Nations, 2008)

Together, these comprehensive legal materials reflect the international consensus about the rules and minimum standards that apply with respect to justice for children. While much of the focus in this Module is on children in conflict with the law, it is important to note that there is there is a wealth of guidance, at the international level, to assist countries in ensuring full respect for the rights of child victims and witnesses.

Justice for child victims and witnesses

Adopted by General Assembly Resolution 40/34 (29 November 1985), the Declaration of Basic Principles of Justice for Victims of Crime, and the implementation documents thereto, establish the broad principles and implementation strategies applicable to victims. More specific guidance on the protection of child victims and witnesses is provided in the Guidelines on Justice in Matters involving Child Victims and Witnesses of Crime (“the Guidelines”), adopted by the Economic and Social Council in resolution 2005/20. These guidelines play an important role in assisting Member States ensure the delivery of effective justice responses, for child victims, that protect children’s rights pursuant to the CRC.

More specifically, the Guidelines set forth good practice with respect to children’s right to be treated with dignity and compassion, the right to be protected from discrimination, the right to be informed, the right to be heard and express views and concerns, the right to effective assistance, the right to privacy, the right to be protected from hardship during the justice process, the right to safety, the right to reparation, and the right to special preventive measures. Further advice on the implementation of the Guidelines at the national level is presented in the Model Law Handbook for Professionals and Policymakers on Justice in matters involving child victims and witnesses of crime.

Guidance Note of the Secretary-General: UN Approach to Justice for Children

Of particular importance, and containing useful guidance regarding the application of the international legal framework on justice for children, is the Guidance Note of the Secretary-General: UN Approach to Justice for Children (United Nations, 2008), which articulates the following aim:

To ensure that children, defined by the Convention on the Rights of the Child as all persons under the age of eighteen are better served and protected by justice systems, including the security and welfare sectors. It specifically aims at ensuring full application of international norms and standards for all children who come into contact with justice related systems as victims, witnesses and alleged offenders; or for other reasons where judicial, state administrative or non-state adjudicatory intervention is needed, for example regarding their care, custody or protection (United Nations 2008).

The approach applies in all circumstances, “including in conflict prevention, crisis, post-crisis, conflict post-conflict, and development contexts” (United Nations 2008).

Outlining strategies for a common UN approach towards justice for children, the Guidance Note elaborates nine Guiding Principles on the basis of international legal standards and norms. Importantly, these principles are meant to guide all efforts relating to justice for children, including both policy work and direct interventions with children.

Guiding Principles of the UN Approach to Justice for Children

- Ensuring that the best interests of the child is given primary consideration

- Guaranteeing fair and equal treatment of every child, free from all kinds of discrimination

- Advancing the right of the child to express his or her views freely and to be heard

- Protecting every child from abuse, exploitation and violence

- Treating every child with dignity and compassion

- Respecting legal guarantees and safeguards in all processes

- Preventing conflict with the law as a crucial element of any juvenile justice policy

- Using deprivation of liberty of children only as a measure of last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time

- Mainstreaming children’s issues in all rule of law efforts

(United Nations, 2008)

Regional standards on justice for children

Complementing the international legal framework on justice for children, standards relevant to the administration of justice for children have also been set at the regional level. In Europe, for example, the Council of Europe has set standards relevant to the administration of justice for children.

European Standards on Justice for Children

The Guidelines on child-friendly justice provide that justice for children should be “accessible, age appropriate, speedy, diligent, adapted to and focused on the needs and rights of the child, respecting the rights of the child including the rights to due process, to participate in and to understand the proceedings, to respect for private and family life and to integrity and dignity” (CoE, 2010, para 1.3). Child-friendly justice is underpinned by the following key principles:

- Participation

- Best Interests of the Child

- Dignity

- Protection from Discrimination

- Rule of Law

Other regions have developed related standards. The Inter- American Court of Human Rights and Inter-American Commission on Human Rights has issued a series of judgements pertaining to the administration of justice for children, pursuant to the Charter of the Organisation of American States (1948) Details on these cases can be found on the website of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights – Rapporteurship on the Rights of the Child.

In Africa, the Guidelines on Action in the Justice System for Children in Africa were adopted in Kampala in 2011. These guidelines aim, inter alia, to support governments in fulfilling their regional and international human rights obligations, with the following scope of application:

- All procedures of an administrative or judicial nature, whether formal or informal, where children are brought into contact with, or are involved in, civil, criminal or administrative law matters, whether as victims or witnesses, alleged offenders, persons who have been convicted or admitted responsibility for an offence or offences, or as subjects in care and protection proceedings or family law or succession and inheritance disputes;

- Traditional justice systems and justice systems of religious courts and bodies;

- All children aged below 18 years living in Africa;

- All violations of rights brought by children to the attention of justice systems (p. 8).

Further normative guidance on justice for children is provided in the Munyonyou Declaration Justice for Children in Africa which serves as a call for action to “[e]nsure that all children enjoy their rights in child justice and that deprivation of liberty is used as measure of last resort (2014, p. 3). In addition, Africa has the only region-specific instrument on child rights. The African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child was adopted in Addis Ababa in 1990 and entered into force in 1999. Article XVII of the Charter enumerates the rights relevant to the administration of juvenile justice, including a range of due process and fair trial rights, and the affirmation that the primary aim of the juvenile justice system is to ensure the child’s rehabilitation and reintegration into his or her family (article XVII (3)). The African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, established in 2001, is mandated, inter alia, with monitoring the implementation of the Charter:

The committee’s main functions are to collect information, interpret provisions of the Charter, monitor the implementation of the Charter, give recommendations to governments for working with child rights organizations, consider individual complaints about violations of children’s rights, and investigate measures adopted by Member States to implement the Charter (African Union website).

The Committee’s 2015-2019 strategic plan includes a situation analysis which notes that while considerable progress has been made in moving towards the establishment of child friendly justice systems in Africa, there is scope to improve implementation and monitoring of children’s rights, and Member States’ compliance with reporting obligations under the Charter (African Committee on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, 2015, p. 6).

Justice for children across various legal domains

Children may be involved in, or seek to be involved in, justice processes across the domains of civil, criminal or administrative law, or as part of formal or informal justice processes that operate at the level of the community or state. While there is considerable variance between the practical operation of legal systems, globally, it is broadly the case that criminal law refers to a body of rules designed to proscribe crimes and regulate proceedings for prosecuting and trying persons accused of such crimes. Civil law is the body of law and procedure that governs relations between private persons or organizations, thus encompassing, inter alia, tort and family law. Administrative law is the body of law and/or regulations that is established and enforced by government institutions.

A comprehensive approach to justice for children requires that the international legal standards enshrined in the CRC are upheld across these respective legal domains. Equal access to justice for all necessitates that child-sensitive statute, procedure, and institutional capacity is operationalized across the civil, criminal and administrative legal domains. For example, as a function of civil law, family law bears particular relevance to justice for children. In many countries there is much work to be done to ensure that child-, gender- and victim-sensitive laws and procedures apply in family law cases, including in matters concerning divorce, child placement and/or child protection.

Administrative law is also an important component of ensuring access to justice for children. Regulations about birth registration, for example, serve a crucial purpose as building blocks for a child’s access to justice.

Birth registration

Children who are not registered at birth are effectively denied a legal identity. Without a birth certificate, children experience difficulties in enrolling in school and in accessing health care and social services. The hardship that this imposes precipitates risks of various kinds:

Knowing the age of children is central to protecting them from violence such as child labour, forcible conscription in armed forces, child marriage, trafficking, and facing trial as an adult (UNICEF, 2013).

The following case is illustrative, involving discrimination on the grounds of sex characteristics, denial of birth registration, and persecution within the criminal justice system.

Example: Denial of birth registration precipitates risks for children

The adverse impacts of being denied birth registration / legal recognition are evident in Muasya v. Attorney General, a case heard in the High Court of Kenya. Born with ambiguous genitalia, Richard Muasya was denied a birth certificate or identity registration card. Unaccepted by his community he left school early, engaged in robbery with violence and, once incarcerated, was subjected to sustained persecution in prison on the basis of his sex characteristics. Indicating the depth of discrimination against intersex individuals, the High Court of Kenya ruled that denial of an identity card did not constitute discrimination or exclusion from legal recognition. The Court did find, however, that the treatment Muasya endured in prison constituted inhuman and degrading treatment, and he was awarded a modest payment of damages (Richard Muasya v the Hon. Attorney General [2010] High Court of Kenya).

For details on a subsequent case, in which a Kenyan baby with intersex characteristics was denied a birth certificate, see CRIN 2015.

The Sustainable Development Goals confirm that birth registration is not an ancillary or inconsequential administrative process, but rather that legal recognition is foundational to justice (conceived in both legal terms and more broadly, as access to equality of opportunity). SDG 16 includes birth registration as a target for achieving strong justice institutions, and SDG Target 16.9 aims to ensure “legal identity for all, including birth registration” by 2030 (Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform). Consistent with article 7 of the CRC, this commitment confirms the importance of birth registration in ensuring a child’s access to justice.

Birth registration is a first step towards safeguarding individual rights and providing every person with access to justice and social services. While many regions have reached universal or near universal birth registration, globally the average is just 71 per cent, on the basis of available country data reported from 2010 to 2016. Fewer than half (46 per cent) of all children under 5 years of age in sub-Saharan Africa have had their births registered. (ECOSOC, E/2017/66 at para 20)

The emphasis that SDG 16 places on birth registration reflects the importance of ensuring that the pathways for children’s access to justice are established early in a child’s life.

In addition to the civil, criminal and administrative jurisdictions, constitutional law has the potential to catalyze justice for children by, for example, incorporating the provisions of ratified international human rights treaties into national law, or by establishing the provisions by which the sitting government can, or should, establish or support national human rights institutions, child ombudspersons, or national plans of action on children’s rights or violence against children.

Furthermore, in addition to the various legal regimes within the national legal jurisdiction, bodies of law (and institutions) at the international and/or regional levels play a powerful role in shaping the procedures relevant to the treatment of children, both during justice processes and more broadly. Consider, for example, the evolving recognition of the importance of establishing standards that uphold the rights of victims (including child victims) in international criminal trials. (Case Study 9 in this Module provides further materials on this topic). Also relevant are the provisions of international humanitarian law and international human rights law. Access to justice is limited for so many children living in settings of active conflict or transitional justice, despite the intersecting bodies of law that provide for their protection. Challenges associated with ensuring the implementation of legal standards in situations of conflict, migration, and transitional justice, are evident in the widespread use of assessments to determine the age of unaccompanied minors in migration contexts, and/or to establish whether undocumented children are above the age of criminal responsibility.

Age assessments

The Committee on the Rights of the Child has provided extensive guidance on the procedures to be followed in instances where a child does not hold formal proof of age by birth certificate. This includes:

- the State’s prompt provision of a birth certificate for the child (free of charge)

- the State’s acceptance of all documentation that can prove age (notification of birth, extracts from birth registries, baptismal or equivalent documents or school reports). These documents should be considered genuine unless there is proof to the contrary.

- the use of interviews with or testimony by parents regarding age or for permitting affirmations to be filed by teachers or religious or community leaders who know the age of the child.

“Only if these measures prove unsuccessful may there be an assessment of the child’s physical and psychological development, conducted by specialist pediatricians or other professionals skilled in evaluating different aspects of development. Such assessments should be carried out in a prompt, child- and gender-sensitive and culturally appropriate manner, including interviews of children and parents or caregivers in a language the child understands. States should refrain from using only medical methods based on, inter alia, bone and dental analysis, which is often inaccurate, due to wide margins of error, and can also be traumatic. The least invasive method of assessment should be applied. In the case of inconclusive evidence, the child or young personis to have the benefit of the doubt.” (General Comment No. 24, 2019, para 33-34)

Key requirements for adopting a comprehensive approach to juvenile justice

The dual role of the juvenile justice system

The international legal framework requires that States afford children specialized justice responses, in recognition of the distinct physical, psychological, emotional and educational characteristics of childhood, and children’s evolving capacities. The specific legal and procedural safeguards enshrined in the CRC, and elaborated in the UN standards and norms on juvenile justice, are an important means of mitigating the harms that can accompany contact with justice processes. But these important safeguards do not obviate the role of the justice system. As established in Topic One of this Module, strong justice institutions that uphold human rights are integral to the promotion of peaceful and just societies, and the rule of law.

The role of the juvenile justice system (the specialized juvenile justice system) is thus dual. The strong legal framework that criminalizes and prosecutes prohibited conduct works in the public interest – by promoting public safety and upholding the rule of law. Importantly, the public interest is also served, by the delivery of fair and humane treatment to individuals (including children) in conflict with the law. This is not only because the rights of vulnerable persons are protected, and their prospects of reintegration heightened, but also because the function of state apparatus, in compliance with the law, engenders a sense of trust in the criminal justice system as a means of distributing transactional justice in accordance with national and international law.

There is, thus, a mutually supportive relationship between the upholding of children’s rights, and the functioning of strong justice institutions that operate in accordance with the law. This is not always understood at the national level, as media and political figures can play a role in fostering a fear of “youth crime”. This can result in calls for tougher responses to children alleged as, accused of or recognized as having infringed the penal law. The dangers inherent in this dynamic have been observed, for many years, by child rights scholars and by the Committee on the Rights of the Child. In General Comment No. 24, the Committee identifies that the negative representations of children in conflict with the law are often based on misconceptions, and there are risks associated with calls for tougher responses to crime (2019, para 111). The Committee confirms that justice responses that priorities the best interests of the child also serve the public interest:

in all decisions taken within the context of the administration of juvenile justice, the best interests of the child should be a primary consideration. Children differ from adults in their physical and psychological development, and their emotional and educational needs … The protection of the best interests of the child means, for instance, that the traditional objectives of criminal justice, such as repression/retribution, must give way to rehabilitation and restorative justice objectives in dealing with child offenders. This can be done in concert with attention to effective public safety. (Committee on the Rights of the Child 2007, para 10)

A specialized system for children should not be perceived as a “soft” or lenient option that protects children but not society. This is a misconception, as a specialized system is founded on responses to offending that preserve public safety, help the child assume a constructive role in society, address their offending behaviour in a manner that is appropriate to their age, maturity and development, and encourage a process of behavioural change by helping the child or young person to feel accountable for his or her actions (Capdevila and Foussard, 2020). A specialized justice system for children has therefore the dual role of preserving public safety while also respecting, protecting and fulfilling the rights of the child (Fedotov, 2017; Weber, Umpierre and Bilchick, 2018; O’Brien, 2020b).

Ecological approach to justice for children

Children who have endured intersecting forms of adversity, violence, and discrimination present with a range of challenges, only some of which are conventionally considered in terms of “justice” responses. This prompts recognition that “access to justice” is very often about access to health, or access to education, or child protection services to safeguard a child from violence or neglect. “Justice” is not a unitary concept that is delivered solely by the application of legal measures.

It is most often the case, for instance, that when a child comes to the attention of authorities it is because there is a problem, or a series of problems, in a child’s life. In some cases, this relates to a child’s behaviours (whether in breach of the penal law, or merely sufficiently problematic to bring a child to the attention of authorities). Where reactionary measures are imposed these are often informed by a “deficit model”, in which the child is framed as a “problematic policy object”. In such circumstances there is a risk that interventions be imposed with haste (whether by law enforcement, judicial actors, or by medical or therapeutic professionals). Although sometimes well-intentioned, efforts to “fix the problem” dominate at the expense of individualized and holistic responses that recognize a child’s participatory rights, their evolving capacities, and the protective factors in a child’s ecology around which strengths-based supports might be built.

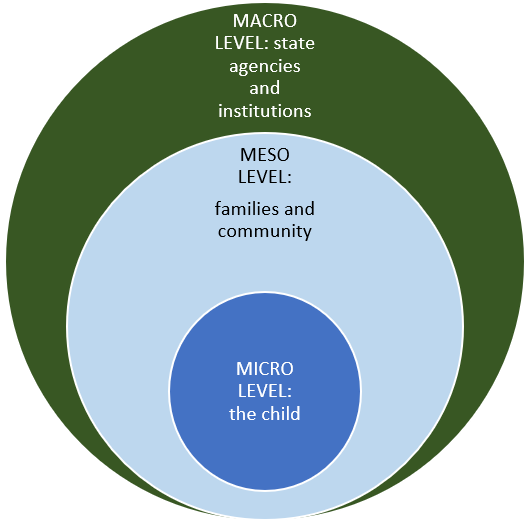

The seminal work of Urie Broffenbrenner established the ecological approach, in recognition of the fact that children are shaped by a range of factors related to their various interpersonal contexts (1979). These contexts may be either proximate (family, friends, school, community) or comparatively distal (state agencies and institutions). Empirical studies have shown that the influence of these interpersonal contexts can act as either risk or protective factors for a child. While this can only be determined by individualized child- and gender-sensitive assessments that are conducted by specialized professionals, for many children, growing up in loving homes with a stable attachment figure can serve as a protective factor, for example. Analysis of a child’s various interpersonal contexts (their ecology) can facilitate an integrated and comprehensive plan to support a child’s development. This functions by bolstering protective factors and implementing non-stigmatizing measures to mitigate the impacts of known risk factors for the child.

Figure 1: Factors relevant to a child’s ecology (UNODC, 2019, p. 71)

Consistent with the impetus to prevent children’s involvement in justice proceedings, the Riyadh Guidelines (GA/Res 45/112, annex, at para 3) place an emphasis on factors known to protect children against involvement in crime (educational opportunities, bolstering a child’s personal development, and addressing the social and structural conditions that shape the motivation, or need, for a child to breach the law). In all, these guidelines take a strengths-based and holistic approach to a child’s development, which recognizes the importance of protective factors within a child’s ecology.

Emphasis should be placed on preventive policies facilitating the successful socialization and integration of all children and young persons, in particular through the family, the community, peer groups, schools, vocational training and the world of work, as well as through voluntary organizations. Due respect should be given to the proper personal development of children and young persons, and they should be accepted as full and equal partners in socialization and integration processes. (GA/Res 45/112, annex, at para 10)

Crime prevention as a core element of a comprehensive approach to justice for children

Building on the understanding about the role that early childhood experiences play in shaping an individual’s wellbeing across the life course, the Committee on the Rights of the Child identifies that prevention and early intervention constitute core elements of a comprehensive child justice approach (General Comment No. 24, 2019, para 9). Developmental crime prevention emphasizes the importance of providing non-stigmatizing and holistic supports to families and communities facing challenges that could compromise a child’s development or well-being. For example, the provision of family supports works in concert with primary health services and education services in community settings, in order to strengthen a child’s ecology. The mutually reinforcing supports increase access to services, and access to justice, for vulnerable children and their families, as Ross Homel describes:

Family support services are among the most common ways that local caring institutions attempt to reinforce the primary care activities of families under pressure. These services are designed to strengthen family relationships and healthy child development through the provision of information, and emotional and instrumental support. Family support incorporates a wide range of service categories that can include counselling and mediation, education and skills development, crisis care and material relief, home-visiting and practical in-home assistance, advocacy, referral to facilitate access to specialized professional services, parent groups, playgroups and in some cases school-based programs like after-school care or breakfast clubs. The work of family support agencies, therefore, can encompass intensive programs tailored to individual family needs, as well as more generic forms. These services are, of course, additional to universal health, social security, preschool and school services, and nearly all aim in one way or another to compensate for deficiencies in these services and to ‘open doors’ to advocate on behalf of children and parents and to improve aspects of local conditions that teachers and community workers know from direct experience are inimical to positive child development (Homel et al, 2015, 2).

While research demonstrates the efficacy of these kinds of supports in preventing children from engaging in activities which would bring them into conflict with the law (Committee on the Rights of the Child, General Comment No. 24, 2019, para 9) the benefits of ensuring a child’s well-being, over the life course, exceed narrow metrics about reduced crime rates. Among the best-known studies in developmental crime prevention, the Perry Pre-School Project provides longitudinal data about the benefits of providing non-stigmatizing supports, and quality early childhood education, to children (and their families) living in poverty. The study, which commenced in the 1960s, involved follow up at various intervals during adulthood of a cohort of children who had been provided with access to quality pre-school education, as well as a cohort who had not received the same supports. By age forty, those who had been provided with quality pre-school education (and accompanying supports for families) went on to graduate from high school; secure higher earnings; and commit fewer crimes, than those who were not provided with the pre-school program (Schweinhardt, 2003).

The efficacy of programmes of this kind points to the importance of promoting public knowledge about the important benefits of non-stigmatizing supports for families. Important, too, is work that challenges prevailing misconceptions about an increased likelihood of criminal involvement for children from large families, children from single parent households, children born out of wedlock, and/or children who come from families that experience economic disadvantage.

Broadly conceived, the preventive dimensions of justice for children are both holistic and tailored to the circumstances of the child and the elements of the child’s ecology (including their family). What this means is that in some instances supports may be required to ensure that a child’s nutritional needs are met (in non-stigmatizing ways) through community or school support networks – even though the link between the provision of food and the provision of justice might not necessarily be immediately apparent. For other families or communities, family days at schools provide a non-stigmatizing means of reaching out to parents who might otherwise be isolated – thereby strengthening formal and informal support networks and fostering community cohesion, both of which contribute to the prevention of crime, and the well-being of children, families, and communities. With an approach of this kind, parents can gain access to a range of services that bolster family functioning, health, and access to justice.

For a study on the delivery of family skills programmes in conflict settings lecturers may wish to refer to the article by El-Khani, et al (2019), which profiles a parenting intervention in the West Bank. Further, UNODC supports Member States in the development and delivery of evidence-based family skills programmes for the prevention of violence, drugs and crime (see also UNODC, 2009).

Protective environment framework

The UN Model Strategies and Practical Measures on the Elimination of Violence against Children in the Field of Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice identify the importance of a “protective environment” (an environment that promotes a child’s well-being) as conducive to ensuring to the maximum extent possible the survival and development of the child, including physical, mental, spiritual, moral, psychological and social development, in a manner compatible with human dignity (UN, 2014, GA Resolution 69/194, para 6 (m)).

While the actors and institutions involved in creating this protective environment framework vary, they may include statutory justice and child protection authorities and institutions (providing these operate according to a rights-based and child-, gender- and victim-sensitive approach). Other institutions and actors include medical professionals, psychologists, social workers, legal representatives, teachers, non-governmental organizations, faith-based organizations, community members, family and peers. The implementation of a protective environment framework is required for all children, at all stages of any process (including administrative, legal, or medical processes).

A protective environment is necessary at all stages of all justice processes, including for crime prevention initiatives, to ensure that protective factors are bolstered, and initiatives do not inadvertently cause harm. In recent years much attention has been directed at developing child-friendly procedures in court settings, as well as the post-hearing or post- sentence phase, to ensure individualized supports for both child victims and children alleged as, accused of or recognized as having breached penal law. In sum, a protective environment is implemented through the provision of integrated supports on the basis of individualized assessments that are conducted in accordance with the CRC general principles of non-discrimination, best interests of the child, the right to survival and development, and the right to be heard. (For more on the right to be heard in judicial proceedings, see Cashmore and Parkinson, 2007; and for a pan European study of child participation in the youth court, see Rap, 2013).

Strengthening child protection systems

The Committee on the Rights of the Child, and the SRSG on VAC has called for the strengthening of national child protection systems, to preclude the inadvertent criminalization of children that require a child protection response:

[T]o prevent the involvement of children in the criminal justice system and lower the risk of related incidents of violence, it is critical to develop a strong and cohesive national child protection system. It is essential to address the root causes of child poverty and social exclusion, and provide access to basic social services of quality to all children, including early childhood initiatives and quality education. In addition, young people at risk need to benefit from targeted support to prevent situations where they may be exposed to violence or involved in criminal activities. (Santos Pais, 2015, p. 22)

A subsequent section of Topic Three identifies various ways in which deficiencies in child protection responses result in net widening, and the unnecessary criminalization of children for behaviours that stem from childhood trauma, exploitation, poverty, or living/working on the streets. In addition, the Committee on the Rights of the Child has emphasized the importance of ensuring that effective child protection responses are provided to children below the minimum age of criminal responsibility (MACR). This is an important means of diverting children from justice-involvement, by providing early supports for a child’s behavioural change, and ensuring that systems neglect does not result in the criminalization of the child once they reach the age at which they may be prosecuted according to criminal law (General Comment 24, 2019, para).

Strong child protection systems are also important for the role they play with respect to justice processes (in both the family and criminal jurisdictions). For example, effective case management ensures that in instances where a child with a history of child protection involvement comes into conflict with the law, the child’s history can be made known to the prosecutor and/or the court, to assist with an application for dismissal or diversion (UNICEF, 2017). Furthermore, child protection professionals play an important role in providing specialized individualized assessments of children for both family law and criminal law proceedings. Where there is limited capacity, these assessments fail to provide a full picture of a child’s history and/or situation. This example points to the clear need for specialized training for child protection professionals, on trauma informed care; on understanding their role vis-à-vis the justice system; and on children’s rights (including the mechanisms by which children’s rights are justiciable within their national context).

There are various additional points at which the statutory child protection and justice systems interact, including with respect to children serving community-based orders while in alternative care; and the involvement of the child protection system in receiving children released from custodial sentence. At each point in the system it is important that there is an integrated and coordinated response, to establish clear lines of responsibility and ensure that children are not left without necessary supports.

Next: Topic four - Justice for children in conflict with the law

Next: Topic four - Justice for children in conflict with the law

Back to top

Back to top