Published in January 2022

This module is a resource for lecturers

Wild flora as the target of illegal trafficking

The issue of “plant blindness”

The first module of the University Series on Wildlife Crime discusses the challenges associated with the available data and estimates regarding the level and patterns of wildlife, forest, and fisheries crime. There is a tendency to attempt to make estimates, but the data gaps are large and there are few reliable statistics.

Margulies et al. (2019) discussed the fact that plants have been largely ignored in research and policy on the illegal wildlife trade (IWT). Even though a wide variety of plant species are being threatened by illegal exploitation or IWT, flora is an often-neglected topic in the research and funding dedicated to understanding, preventing and combating the illegal trade in wildlife, with issues relating to timber perhaps constituting an exception. Margulies et al. (2019) refer to this as an example of “plant blindness”, a term that was coined earlier by other authors, which refers to the “misguided anthropocentric ranking of plants as inferior to animals” (Wandersee and Schussler, 1999, p. 82). Within wild flora, most research has focused on deforestation and the related issue of illegal logging, and by extension this has led to a geographically constrained focus, with most attention on tropical forests (Goettsch et al., 2015). Flora species from all ecosystems, including cacti that grow in arid lands, are affected and so also require consideration (Goettsch et al., 2015).

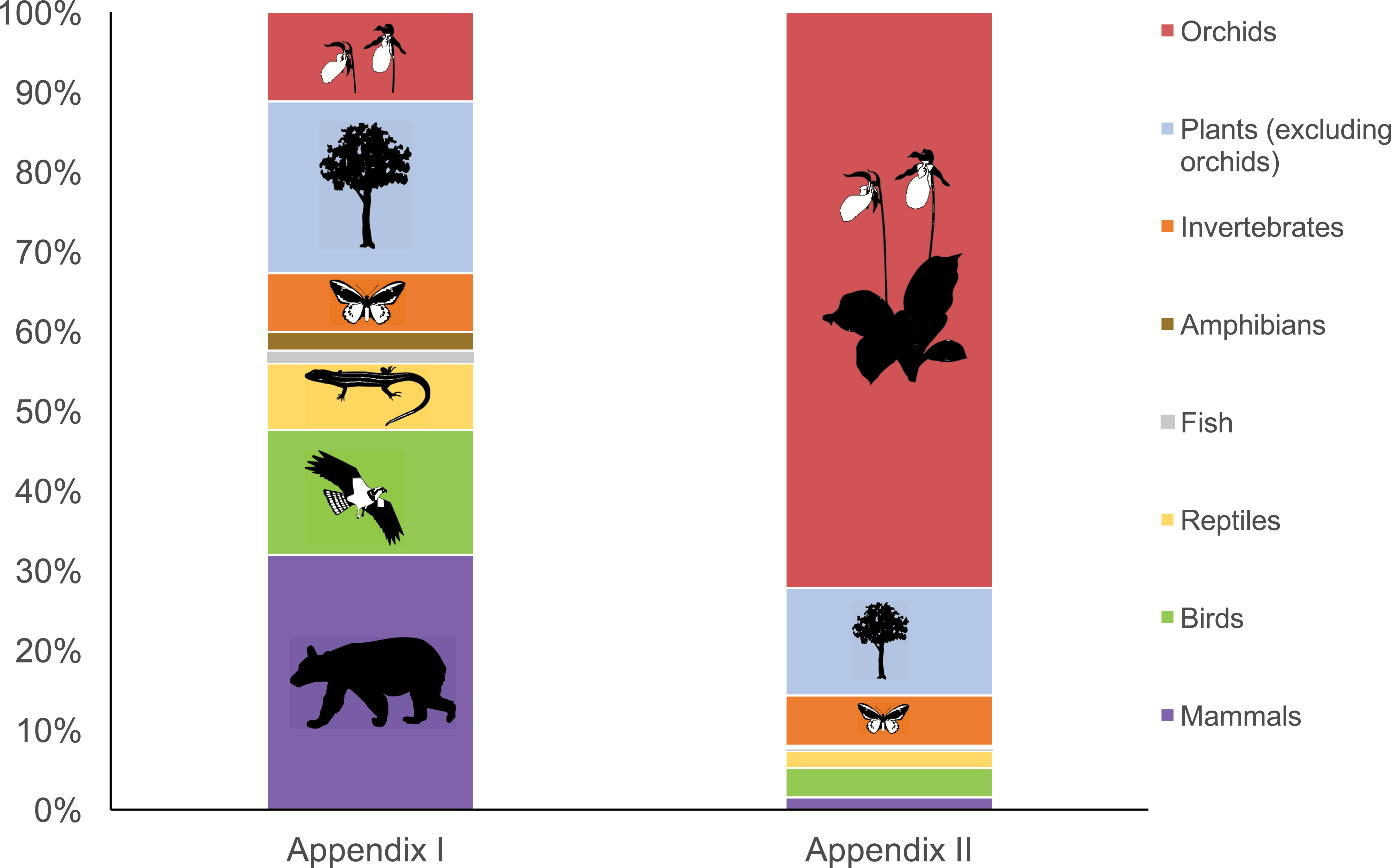

This lack of data and research is particularly puzzling given that plants constitute a large percentage of the species protected by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (CITES). Across its three appendices, CITES regulates international trade in flora and fauna in an attempt to ensure sustainability of such trade. Flora represents 37% of the roughly 1,100 species protected in Appendix I, which lists the most endangered species, and 86% of the over 37,000 species protected in Appendix II, which lists species not necessarily threatened but may become so unless trade is closely controlled. The figure below clearly illustrates the relative weight of flora (orchids and plants) among the species protected by the Convention. For more information on CITES please refer to the E4J Module on International Frameworks for Combating Wildlife Trafficking.

Figure 1 - Taxonomic breakdown of CITES Appendices I and II. From Hinsley et al. (2018, p. 441)

Estimated size of the illegal market

In the case of illegal exploitation of wild flora, the problem of reliable data is particularly manifest with plants. Not much systematic research has been done on this issue. As noted by Goettsch et al. (2015), the global status of plant species, and the likelihood of their extinction in the near future, remains poorly understood, despite the general importance of plants for ecosystems.

In addition to the legal trade, often through nurseries, there also exists an illegal trade in wild-sourced plants. Goettsch et al. (2015) found that 86% of threatened cacti used in horticulture were extracted from wild populations. Phelps and Webb (2015), in the first in-depth study of the trade of wild-collected ornamental plants in continental Southeast Asia, discovered that there is a large degree of underreporting of the illegal trade in ornamental plants. The observed cross-border trade was orders of magnitude larger than the government-reported CITES statistics. The authors found a massive, previously undocumented, commercial trade in wild, protected ornamental plants involving Thailand, Lao PDR and Myanmar. Hinsley (2018), who looked at the role of online platforms in the illegal orchid trade, found that there is considerable overlap between the legal and illegal online trade.

The problem of lack of reliable data also exists with regard to the illegal logging and related timber trade, but much less so compared to non-timber flora. The larger focus on timber-issues within the realm of wild flora could potentially be explained by the fact that illegal logging entered the international political agenda earlier due to the large-scale timber operations, visible impact on rainforests, use of violence and overall economic importance of the sector. Hence, much more scientific knowledge of illegal timber markets is available than on illegal plant markets. For example, over one hundred scientific publications can be found in which illegal logging is discussed, mostly in forestry and natural science journals (for an overview see Kleinschmit et al., 2016). There have been a fair number of criminological publications on illegal logging and deforestation since the 2000s (Boekhout van Solinge 2008; Graycar and Felson 2010; Bisschop 2012, 2013, 2015; Wyatt 2014; Cao 2018; Wagner et al., 2020). Nevertheless, the 2016 International Union of Forest Research Organizations Expert Panel on Illegal Timber Trade noted that severe data gaps exist in measuring illegal logging and related timber trade. Estimates of the global market value of the illegal logging and illegal timber trade range from USD 10 billion to USD 100 billion annually (Kleinschmit et al., 2016).

Example: Deforestation as an indicator of threats to wild flora

The exploitation of wild flora and forests, notwithstanding whether it is legal or illegal, is promoting and driving forest fragmentation, forest degradation, deforestation, and the associated loss of flora biodiversity. Between 2015 - 2020, the annual global rate of deforestation was estimated to be 10 million hectares, while primary forests had declined by 80 million hectares since 1990. It is difficult - if not impossible - to establish the extent to which deforestation is driven by legal or illegal activities. In some key rainforest countries, illegal logging is estimated to account for 35 to 90 per cent of all forestry activities, although precise numbers are lacking. This lack of precision in the estimates can likely be explained by the limited –or absent– land registry systems around the world.

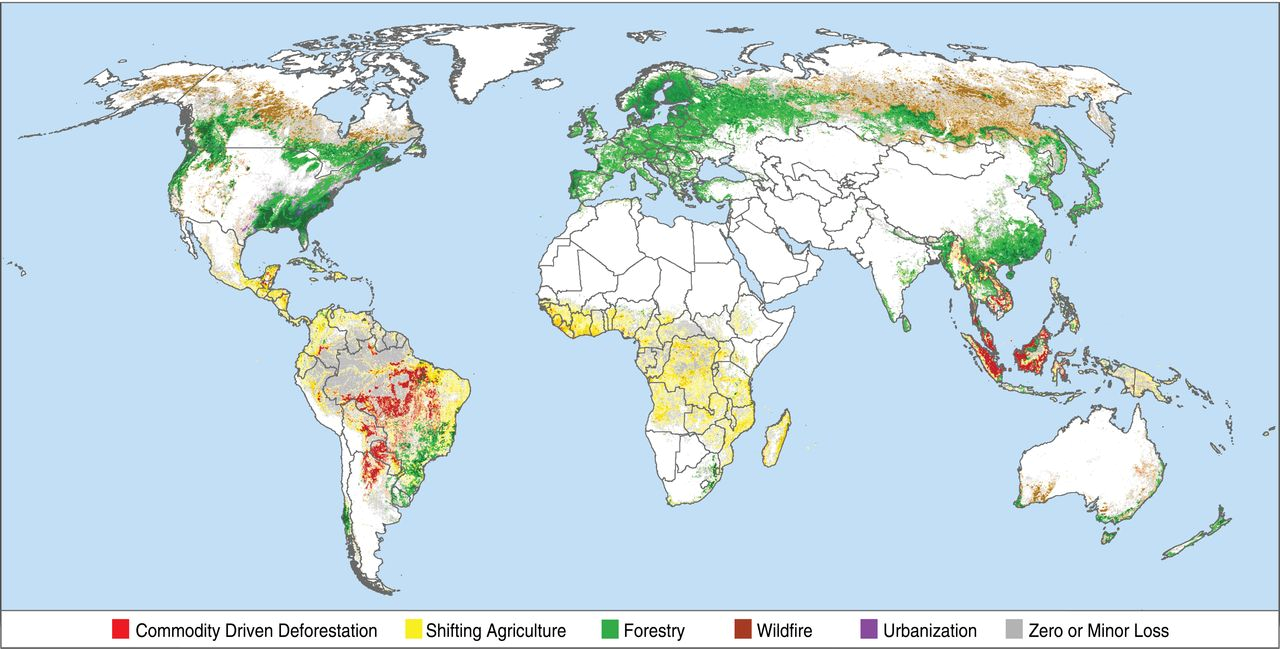

Notwithstanding the challenges in gauging illegality, deforestation and forest cover loss can shed some light on the scale and scope of threats to wild flora. Satellite imagery allows the identification of geographical differences between drivers of deforestation. Figure 1 (below) provides an overview of the different drivers of forest cover loss between 2001-2015. The term “forestry” describes large-scale forestry/logging operations that take place within managed forests.

Graph 1 - Primary drivers of forest cover loss between 2001-2015. Source: Curtis et al. (2018: 1110)

While forest cover loss is a useful indicator of threats to wild flora, not all illegal activities that exploit wild flora cause deforestation, making it an imperfect estimate of the magnitude of the problem. For example, illegal harvesting of plants or certain species of trees within a forest might not cause complete deforestation yet can have devastating impacts on the functionality of the ecosystem as a whole.

(Gan et al., 2016 ; Curtis et al., 2018 ; FAO and UNEP, 2020)

Next: Purposes for which wild flora is illegally targeted

Next: Purposes for which wild flora is illegally targeted

Back to top

Back to top