Abena’s four year-old son sits in her lap, and calmness washes over him. As she holds on tightly, he falls asleep.

Just a few months ago, this wouldn’t have been possible.

Abena is a prisoner at Sunyani Female Prison. Until recently, children were not allowed to visit the prison for fear of ‘contamination’, and the only contact between them and their parents took place through a window. They could never touch.

Today, as a result of a policy directive from the Director-General of Prisons, visits by children are encouraged – an innovation in Ghana’s female prisons that has improved prisoner morale, strengthened their ties with family members, and brought Ghana in line with international standards and norms, such as the Bangkok Rules.

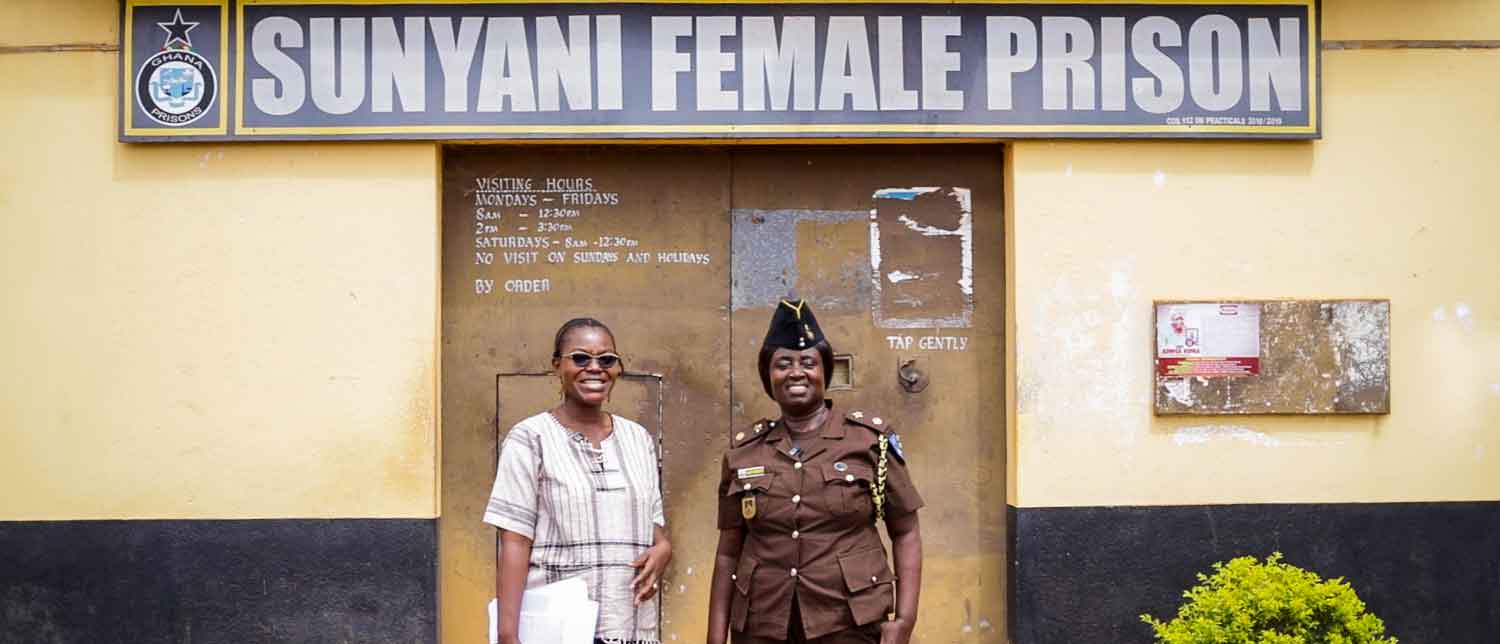

The change came about in part due to the advocacy of Chief Superintendent Mary Asante Sarfo, Officer in Charge of Sunyani Female Prison, who is one of a small but growing number of female senior figures in Ghana’s prison service. In the complex world of prison administration, where maintaining security is sometimes perceived to clash with the need for humane treatment, Mary has emerged as an inspirational leader.

Mary began her journey with the Ghana Prisons Service in 1985, despite skepticism from her friends and community. Enlisting as a recruit from her earlier career as a teacher, she joined a field where women were significantly underrepresented. In her recruitment year, there were only 33 women to 125 men.

Starting her career at Nsawam Medium-Security Prison (Male), Mary discovered that women were confined to office roles, excluded from direct prisoner management. Undeterred, she pushed for opportunities to engage in yard duties and headcounts, with support from her male counterparts.

"The prisoners were eager to see a female officer, and everybody wanted to get closer to share his story," she recalls.

“The law is there but we also look at the human aspects and treat them as people,” says Mary.

She seeks to maintain order through respecting prisoners' dignity, prioritizing empathy and communication. She emphasizes that, in her experience, empathy does not undermine authority but rather enhances it by fostering trust and cooperation. Regular communication with prisoners, understanding their concerns and stress, and addressing their needs are practices Mary has ingrained in the prison's culture.

This approach is in harmony with the United Nation Minimum Standards for the Treatment of Prisoners – known as the Nelson Mandela Rules. These rules provide the blueprint for good, rights-respecting prison management in the 21st Century, and Mary has been a tireless advocate for them. Mary credits a training from the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) with helping her bring the Mandela Rules to life in Sunyani Female Prison.

Abena’s experience is testament to the power of this approach: "Because of the way they relate to us, even if you are a difficult person, you will change.”

Mary adds, “The fact that they have been incarcerated doesn’t mean that they have lost their rights. You must first and foremost know that they are human beings.”

Chief Superintendent Mary Asante Sarfo, Officer in Charge of Sunyani Female Prison

Prisoners at the Sunyani Female Prison in Ghana

Mary remembers when she was posted to the Sunyani Female Prison as a junior officer in 1993. At that time, she and the Officer in Charge introduced dressmaking and kenkey (a Ghanaian dish) - making programs for prisoners. These programs have expanded over the years to include a bakery, a tailoring shop, and a salon. Understanding that most prisoners lack literacy or vocational skills, she has championed programs aimed at equipping them with the knowledge and skills necessary for their reintegration into society, in line with the vision of the Prisons Service.

While in prison, Abena received training in hairdressing and beading, and now teaches her fellow prisoners so that they too can learn a trade.

Afua, another prisoner, has also benefited from vocational training provided in the prison. “They gave me the opportunity to choose what I wanted to learn and for me, it was professional catering skills even though it was not part of what was typically on offer,” she says.

Mary and her colleagues went the extra mile to seek community collaboration, affording Afua access to catering lessons. This training has allowed her to focus on creating a better future for herself and her three children. “If I’d had that guidance and training before, I probably would not have ended up in prison.”

The treatment of prisoners is important not only for their sake, but for their families, communities, and wider society.

Afua, who lacked substantial family support, found a new family within the prison that has allowed her and her children to thrive following her release.

She describes how her baby’s life began in prison, with hospital arrangements put in place for the birth, frequent visits, and external childcare support arranged after the baby was weaned that continued after her release.

"Not only did Mary arrange for me to see my baby, but when Christmas came, she got some items for the child. The prison staff also showed me the videos of their check-ins with my baby."

Abena’s aunt Agnes has witnessed a remarkable transformation in Abena since her time in the Sunyani Female Prison. She observes that Abena has become "a much calmer and more responsive person… and has something to look forward to.”

Abena looks forward to her release to be able to be with her family fully and to use the training and skills she has acquired to lead an engaged and fulfilled life. She also hopes that her family and society will not stigmatize her. “Prison is not the way we think it is. When a person is released from prison, they need to be fully accepted back.”

Today, Mary mentors aspiring female officers, helping them navigate the challenges of a career in the prison service. She has also become a role model in her community, where her peers now aspire for their children to join the prisons service because of her.

Championing the Nelson Mandela and Bangkok Rules, Mary’s work has demonstrated the importance of healthy family relations for successful rehabilitation of prisoners, together with the power of humane treatment. “If I should die and come again and I’m asked to choose a Service, it would be the Prisons Service, and none other than Ghana Prisons Service,” she says, smiling.

Afua looks back on her time in prison, remembering the care Mary and other prison officials showed her. “I felt a lot of hope,” she says.

Abena’s family, too, feels hope for the future. “When I visit my mum, I can see her clearly, I can see her face well. It is no longer through a window and that makes me very happy,” shares one of Abena’s other children.

Agnes, Abena’s aunt, believes that caring and rehabilitative prisons make a world of difference for prisoners by breaking negative cycles and setting the next generation up for better lives.

“The children of prisoners could grow up to be successful individuals,” she says, “even presidents, like Mandela.”

With thanks to the Ghana Prisons Service for their joint collaboration on the story and our donor the Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs in the U.S. Department of State.

________________

*Pseudonyms have been used to protect the identity of prisoners and former prisoners and family.

UNODC works with over 50 Member States around the world to reduce the scope of imprisonment, strengthen prison management and improve prison conditions, and foster the social reintegration prospects of offenders. Find out more.