Background

Piperazines have been described as ‘failed pharmaceuticals’, as some had been evaluated as potential therapeutic agents by pharmaceutical companies but never brought to the market [1]. One piperazine that has been commonly used as NPS is 1-benzylpiperazine (BZP) though other piperazine derivatives have also been reported. These include among others 1-(3-chlorophenyl) piperazine (mCPP), 1-(3-trifluoromethylphenyl) piperazines (TFMPP), 1-benzyl-4-methylpiperazine (MBZP), 1-(4-fluorophenyl) piperazines (pFPP) and 1-cyclohexyl-4-(1,2-diphenylethyl) piperazine (MT-45).

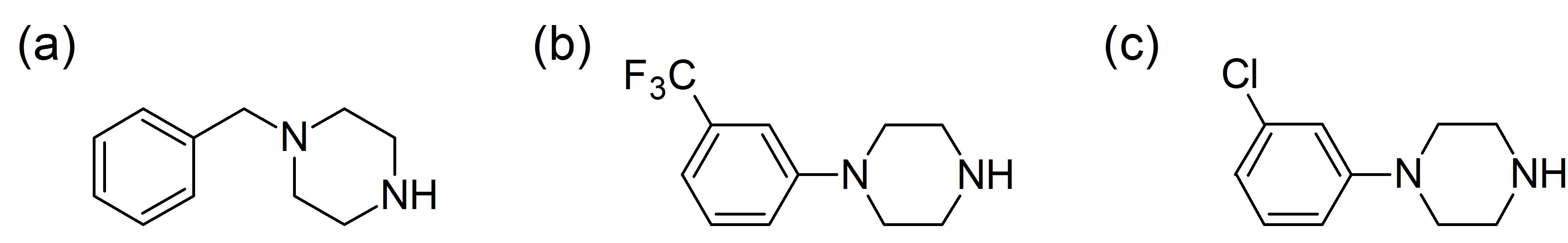

Figure 1 Description of most common piperazines: (a) 1-benzylpiperazine (BZP),

(b) 1-(3-trifluoromethylphenyl) piperazine (TFMPP) and (c) 1-(3-chlorophenyl) piperazine (mCPP)

BZP itself was initially developed as a potential antidepressant drug, but was found to have similar properties to amphetamine and therefore liable to abuse. In the 1980s, it was used in Hungary to manufacture piberaline, a substance marketed as an antidepressant, but later withdrawn [2]. In the late 1990s, BZP emerged in New Zealand as a ‘legal alternative’ for MDMA and methamphetamine [3]. In Europe, its use was first reported in Sweden in 1999, but it only became widespread as a NPS from 2004 onwards until controls over the substance were introduced in 2008, in the European Union [4].

mCPP, was developed during the late 1970s and is used as an intermediate in the manufacture of several antidepressants, e.g. trazodone and nefazodone [5]. TFMPP is almost always seen in combination with BZP to produce the entactogenic [6] effects of MDMA [7].

Neither BZP nor any other piperazines are under international control, although several (BZP, TFMPP, mCPP, MDBP) were pre-reviewed by the WHO Expert Committee on Drug Dependence in 2012. Several countries have introduced national control measures over piperazines.

Description

Piperazines are frequently sold as ‘ecstasy’. Some of the generic names for these substances include, ‘pep pills’, ‘social tonics’ or simply ‘party pills’. The latter term was used to commercialize BZP in New Zealand [8]. Other street names include Jax, A2, Benny Bear, Flying Angel, Legal E or Legal X, and Pep X, Pep Love or Nemesis [9]. MCPP is known as 3CPP, 3C1-PP or CPP.

Piperazines are usually available in the form of pills (regularly pressed with logos similar to ecstasy pills), capsules or loose powders, and are mainly consumed by ingestion. Liquid forms are rarely seen, but injection, smoking and snorting is also possible.

Most piperazines act as central nervous system stimulants. In rare cases (e.g. MT-45), they can also act as opioids. Stimulants mediate the actions of dopamine, norepinephrine and/or serotonin, mimicking the effects of traditional drugs such as cocaine, amphetamine, methamphetamine, and ecstasy. Opioids belong to a chemically diverse group of central nervous system depressants. They bear structural features that allow binding to specific opioid receptors, resulting in morphine-like effects e.g. analgesia.

Reported adverse effects

Piperazines have been found to act as stimulants as a result of dopaminergic, noradrenergic, and predominantly serotoninergic effects produced in the brain. The majority of pharmacological studies of piperazines have focused on BZP and have indicated that it produces toxic effects similar to amphetamine and other sympathomimetics. According to animal studies, its effects are less potent than amphetamine, methamphetamine and MDMA [10]. TFMPP, used in conjunction with BZP, has been reported to produce some of the effects of MDMA, but with a lower potency [11], while mCPP has been indicated to produce similar stimulant and hallucinogenic effects as MDMA [12].

In New Zealand, toxic seizures and respiratory acidosis after the use of BZP alone or in conjunction with other drugs were reported from three patients [13]. Another study of 61 patients reported toxic effects of BZP, with two cases presenting life-threatening toxicity [14]. Hyperthermia, rhabdomyolysis and renal failure associated with BZP ingestion have also been reported [15]. In the United Kingdom, self-terminating grand mal seizures [16] after the use of BZP have also been reported [17].

Several fatal cases involving piperazines use were reported in Europe. Two of the cases involved the use of BZP in conjunction with TFMPP and none referred to the use of piperazines alone [18]. BZP and TFMPP were also associated with 19 fatalities between 2007 and 2010 [19]. While reported effects of mCPP include serotonin syndrome, no fatal poisonings from mCPP have been reported so far [20]. Similarly, toxic effects from the use of TFMPP alone have not been documented [21].

References

[1] King, L.A and A.T. Kicman, “A brief history of ‘new psychoactive substances”, Drug Testing Analysis 3 (2011): 401-403.

[2] European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), “EMCDDA Risk Assessments: Report on the risk assessment of BZP in the framework of the Council decision on new psychoactive substances”, Germany, 2009.

[3] “Approximately 1.5 to 2 million tablets had been manufactured by Vitafit Nutrition Ltd. for Stargate International (one of the major distributors in New Zealand) since 2001” in “The Expert Advisory Committee on Drugs (EACD) advice to the Minister on: Benzylpiperazine (BZP)”, New Zealand, April 2004; Industry figures point out that 26 million doses were sold over an 8-year period; Stargate International, “Party pills: successful safety record”, Press Release, 13 March 2008.

[4] European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), “EMCDDA Risk Assessments: Report on the risk assessment of BZP in the framework of the Council decision on new psychoactive substances”, Germany, 2009.

[5] Fong, M.H., Garattini, S. and Caccia, S., “1-m-Chlorophenylpiperazine is an active metabolite common to the psychotropic drugs trazodone, etoperidone and mepiprazole”, Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 34 (1982): 674-5.

[6] “Entactogens evoke mainly pleasant emotional effects of relaxation, feelings of happiness, increased empathy, and closeness to others” in Downing, J., “The psychological and physiological effects of MDMA on normal volunteers”, Journal Psychoactive Drugs 18.4 (1986): 335-40; Greer, George, et.al., “Subjective reports of the effects of MDMA in a clinical setting”, Journal Psychoactive Drugs 18.4 (1986): 319-27; Liester, M.B., Grob, C.S., Bravo, G.L. and Walsh, R.N., “Phenomenology and sequelae of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine’, Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 180. 6 (1992): 345-52; Hermle, L., et.al., “Psychological effects of MDE in normal subjects. Are entactogens a new class of psychoactive agents?”, Neuropsychopharmacology 8.2 (1993): 171-76; Cohen, R.S., “Subjective reports on the effects of the MDMA (“Ecstasy“) experience in humans”, Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatryis 19.7 (1995): 1137-45; Vollenweider, F.X., Gamma, A., Liechti, M. and Huber,T., “Psychological and cardiovascular effects and short-term sequelae of MDMA (“ecstasy“) in MDMA-naive healthy volunteers”, Neuropsychopharmacology 19.4 (1998): 241-51 as cited in Euphrosyne Gouzoulis-Mayfrank,, “Differential actions of an entactogen compared to a stimulant and a hallucinogen in healthy humans”, The Heffter Review of Psychedelic Research 2 (2001): 64-72.

[7] Wilkins, C., et.al., (2006), “Legal party pill use in New Zealand: Prevalence of use, availability, health harms and ‘gateway effects’ of benzylpiperazine (BZP) and triflourophenylmethylpiperazine (TFMPP)” Centre for Social and Health Outcomes Research and Evaluation (SHORE), Auckland, New Zealand.

[8] Stargate International, “Party pills: successful safety record”, Press Release, 13 March 2008.

[9] Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), Office of Diversion Control, “N-Benzylpiperazine. (Street Names: BZP, A2, Legal E or Legal X)”, March 2014; European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), “EMCDDA Risk Assessments: Report on the risk assessment of BZP in the framework of the Council decision on new psychoactive substances”, Germany, 2009; World Health Organization (WHO), “N-benzylpiperazine (BZP): Pre-Review Report”, Expert Committee on Drug Dependence, Thirty-fifth Meeting”, Hammamet, Tunisia, 4-8 June 2012.

[10] Elliott, S., “Current awareness of piperazines: pharmacology and toxicology”, Drug Testing and Analysis 3 (2011): 430-8.

[11] Baumann, M., et.al., “Effects of ‘Legal X’ piperazine analogs on dopamine and serotonin release in rat brain”, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1025 (2004): 189-97; Baumann, M., et.al., “N-Substituted piperazines abused by humans mimic the molecular mechanism of 3,4- methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, or ‘Ecstasy’)”, Neuropsychopharmacology 30 (3) (2005): 550-60.

[12] Tancer, M.E. and Johanson, C.E., “The subjective effects of MDMA and mCPP in moderate MDMA users”, Drug and Alcohol Dependence 65 (97) 2001. Cited in Elliott, S., “Current awareness of piperazines: pharmacology and toxicology”, Drug Testing and Analysis 3 (2011): 430-8.

[13] Gee, P., Richardson, S., Woltersdorf, W. and Moore, G., “Toxic effects of BZP-based herbal party pills in humans: a prospective study in Christchurch, New Zealand”, New Zealand Medical Journal 118 (Dec 2005): 1227.

[14] Gee, P., Richardson, S., Woltersdorf, W. and Moore, G., “Toxic effects of BZP-based herbal party pills in humans: a prospective study in Christchurch, New Zealand”, New Zealand Medical Journal 118 (Dec 2005): 1227.

[15] Gee, P., Jerram, T. and Bowie, D., “Multiorgan failure from 1-benzylpiperazine ingestion–legal high or lethal high?”, Clinical Toxicology 48 (2010): 230-3.

[16] “A generalized tonic-clonic seizure is a seizure involving the entire body. It is also called a grand mal seizure. The terms ‘seizure’, ‘convulsion’, or ‘epilepsy’ are most often associated with generalized tonic-clonic seizures”; United States National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health (NIH) accessed at http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000695.htm

[17] Wood, D.M., et.al., “Dissociative and sympathomimetic toxicity associated with recreational use of 1-(3-trifluoromethylphenyl) piperazine (TFMPP) and 1-benzylpiperzine (BZP)”, Journal of Medical Toxicology 4 (2008): 254-7.

[18] Elliott, S., Smith, C., “Investigation of the first deaths in the UK involving the detection and quantitation of the piperazines BZP and 3-TFMPP”, Journal of Analytical Toxicology 32 (2008): 172; Wikstrom, M., Holmgren, P. and Ahlner, J., “A2 (N-Benzylpiperazine) a new drug of abuse in Sweden”, Journal of Analytical Toxicology 28 (2004): 67; Balmelli, C., Kupferschmidt, H., Rentsch, K. and Schneemann M., “Fatal brain edema after ingestion of ecstasy and benzylpiperazine”, Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift 126 (2001): 809-11.

[19] Elliott, S., “Current awareness of piperazines: pharmacology and toxicology”, Drug Testing and Analysis 3 (2011): 430-8; for more information on fatalities related to BZP see World Health Organization (WHO), “N-benzylpiperazine (BZP): Pre-Review Report”, Expert Committee on Drug Dependence, Thirty-fifth Meeting”, Hammamet, Tunisia, 4-8 June 2012.

[20] European Momitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), “BZP and other piperazines”. Available at http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/drug-profiles/bzp

[21] Elliott, S., “Current awareness of piperazines: pharmacology and toxicology”, Drug Testing and Analysis 3 (2011): 430-8.