Nha Trang City (Viet Nam), 16-17 December 2020 - Public procurement is a serious corruption risk, leading to losses of an average of 10-25% of a contract’s value. A recent UNODC study found that the spread of Covid-19 across Southeast Asia has only served to heighten such risks, due to an combination of limited transparency, rapidly increased public spending and relaxed integrity and compliance checks.

To enhance the integrity of public procurement in Viet Nam, UNODC has been working with the Ministry of Agriculture & Rural Development (MARD), through high-level advocacy and trainings for investigative officers funded by the UK Government. In July of this year, UNODC and MARD co-launched a Guide on Inspecting for Procurement Corruption and Fraud in the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, adopted by the Ministry as the official training manual to be used in all of Viet Nam’s 63 provinces.

Building on this momentum, over 16-17 December 2020, UNODC held a multi-agency training on Addressing Corruption Risks in Public Procurement. The event brought together 34 middle and high-level inspectors from key government agencies in the South of Viet Nam, to raise awareness about corruption in procurement and to institutionalize best practices on its prevention and investigation.

Inspectors at training on corruption in procurement

Key issues highlighted in the training include:

Corruption May Pervade Multiple Stages of the Procurement Process

Public procurement processes can be categorized into three stages: pre-tender, tender/evaluation and award, and the post-tender/contract administration phase – each which are associated with distinct corruption risks:

In the pre-tender stage, award criteria may be manipulated to allow too much discretion, or else may be too restrictive in order to favour a particular supplier. Procurement staff may engage in contract splitting in order to stay below certain monetary thresholds, in order to retain the freedom to select a preferred bidder. The quantity needed by the tender may also be inflated so as to divert funds to specific individuals.

In the evaluation or tender stage, bidders may collude in effort to avoid competition or to artificially inflate the prices of goods or services. Tactics to achieve this may include the use of complementary bids (i.e. the submission of “fake” bids to give the illusion of competition), bid rotation (conspiring to alternate bids), bid suppression (agreeing to withdraw a previously submitted bid or to refrain from bidding) or market division (refraining from competing in a designated portion of the market, e.g. among certain geographic areas or customers).

Meanwhile, at the contract administration stage, the assessment of contract deliverables – including quality control – may be influenced by bribery. Further funds may be channeled to the winning bidder through cost mischarging, where the procuring entity is charged for ineligible costs.

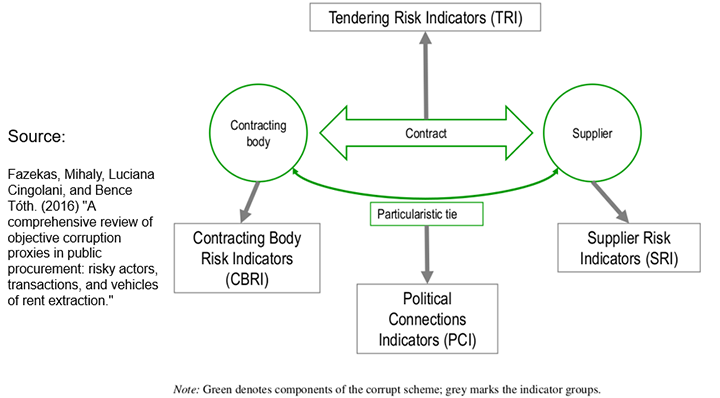

At the same time, corrupt practices often spread across multiple stages of the procurement process. One way of analyzing this is by examining the risks associated with the actors involved, rather than by tender stage alone (see below). Corruption may be identified through signs that the procurement process has been manipulated (tendering risk indicators), evidence of ties between bidders and those in public office (political connection indicators), the use of winning companies as vehicles of rent extraction, or for the distribution/hiding of assets (supplier risk indicators), or there may be signs that the contracting body is unable to resist pressure to favor a connected bidder (contracting body risk indicators).

Visualization of types of risks associated with corruption in procurement, presented by Prof. Lucio Picci

Identifying Corruption through Red Flags, Price Standardization and Probabilistic Auditing

Where there is a lapse in the following of correct procedures, e.g. through contract splitting, this may be due to reasons other than corruption, such as well-intentioned efforts to “cut red tape” or an “honest mistake”. To assess the presence of corruption, inspectors may look to deviations in market prices and departures from average behaviours, drawing on a broad array of data.

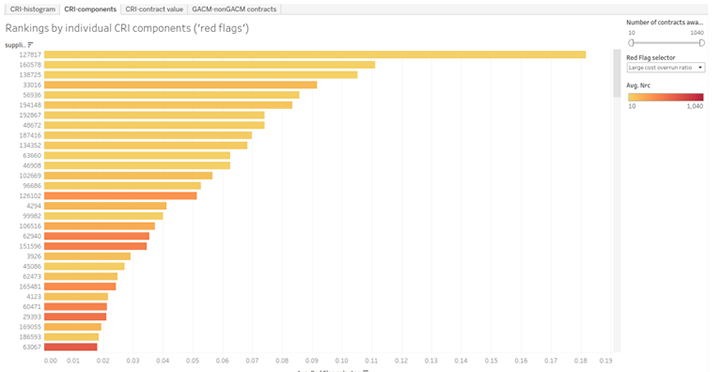

Red flags can help to emphasize the likelihood of improper behaviour across a sliding scale, through what is known as probabilistic auditing. One advantage of this approach is that where corruption is gauged using concrete, binary criteria, it may incentivize corrupt persons to manipulate reporting documents in order to appear to stay beneath the threshold. Instead, probabilistic auditing encourages inspectors to look holistically at different elements of the bidding process, and to look intuitively at tenders based on the likelihood of suspicious activity. To apply this, analysts might develop a Corruption Risk Index (CRI) in which each identified risks (e.g. the number of successful bids won per company) increase the ranking of a company along a graduated scale (see below).

Algorithmic analysis of bidding by M. Fazekas in OECD (2020), presented by Prof. Lucio Picci

The Added-Value of Civic Monitoring

Research shows that, for earthquakes of a given magnitude, places with higher corruption are correlated with more deaths. One key reason for this is that the prevalence of corruption frequently leads to sub-optimal construction outcomes, as money set aside to meet safety standards is skimmed off.

The work which state inspectors do to assess the quality of goods and services can be supported by innovative schemes to promote public scrutiny. This can enhance effective outcomes, since assessing the quality of goods and services in many instances is difficult to determine in the short-run. Indeed, in Article 13 of the United Nations Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC), States pledge to fight corruption through the “active participation of individuals and groups outside the public sector, such as civil society, non-governmental organizations and community-based organizations.“

Other Useful Links: